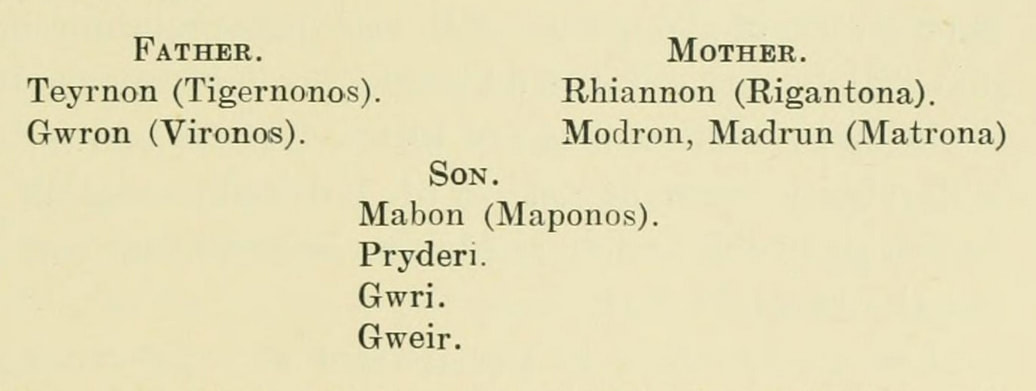

Modron is widely considered to be cognate with Dea Matrona of Gaul, the tutelary goddess of the River Marne. (Both names essentially mean “divine mother”.) She is also related to an early Celtic saint named as Modrun, Madryn, Materiana, etc. in Wales, Brittany, and in Cornwall, where she has a famous holy well.

The tale goes as follows:

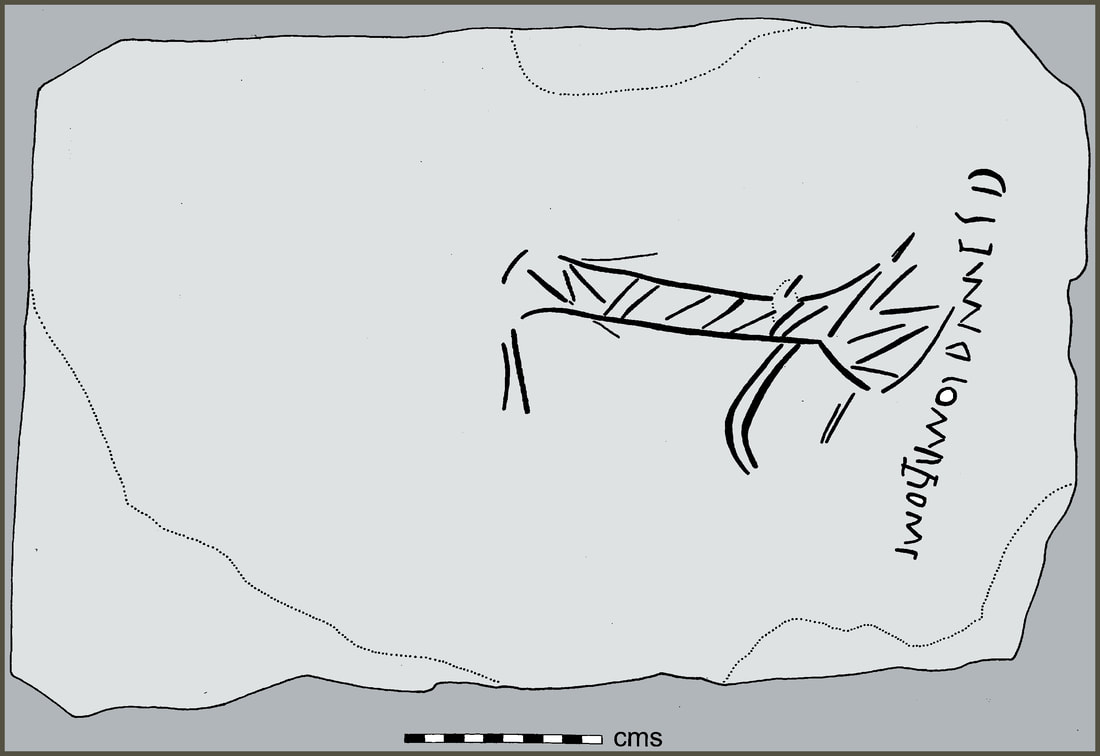

Urien is told that at a certain river ford, all the dogs of the district go to bark, as if they see something uncanny, which no human can see. Urien approaches the ford and the barking stops. He looks around, and sees a young woman washing clothes in the river. He is consumed with desire for the woman, and has sex with her – whether with or without her consent is somewhat ambiguous.

Immediately after this act, the woman blesses Urien and thanks him, and tells him that she was fated to wash at that place until she got a son “by a Christian”. Modron then introduces herself by name and says that she is the daughter of Avallach (Triads), the king of Annwfn (Pen. 147). She tells Urien to return in a year’s time and she will give him their son. When he does so, she actually presents him with twins – a son, called Owein, and a daughter, called Morfydd.

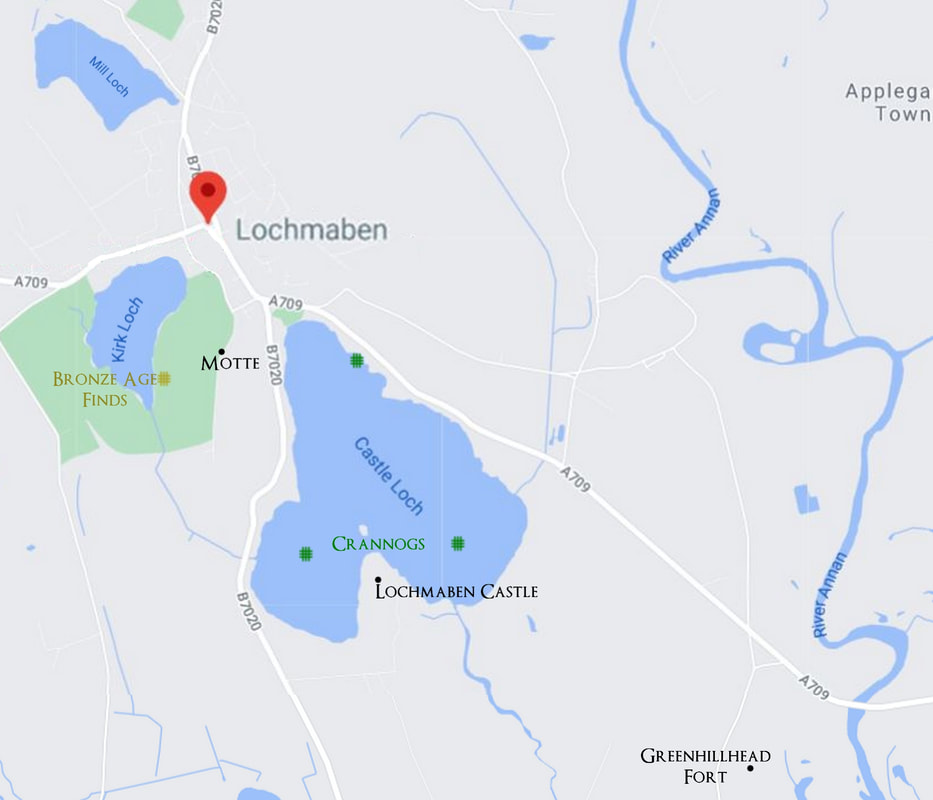

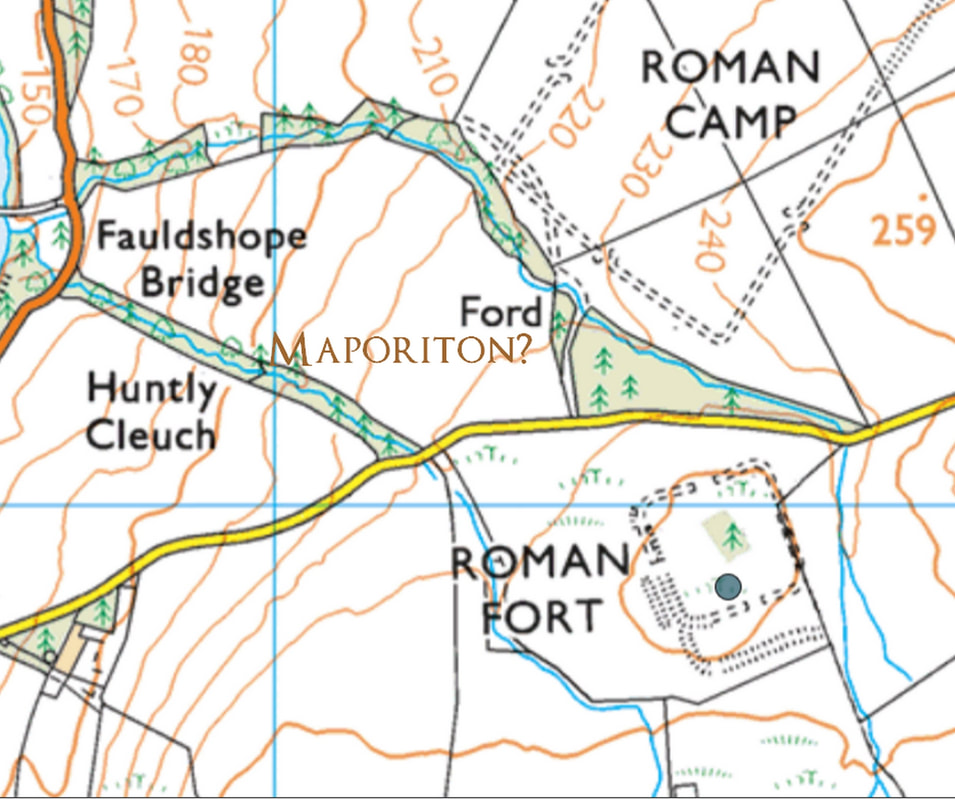

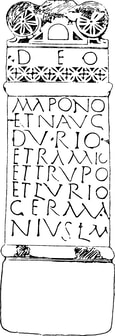

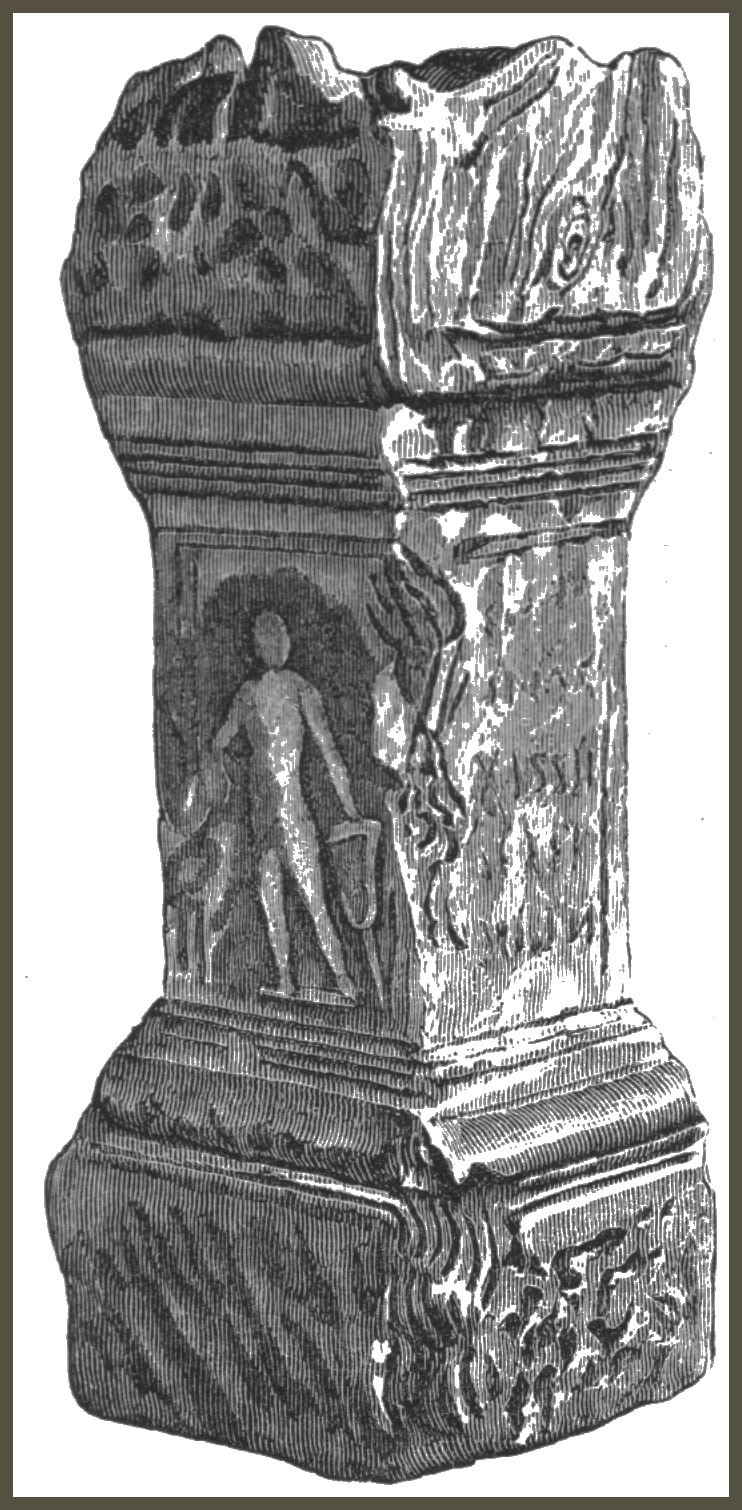

There is no more to the story than this, but there is some poorly preserved folklore in Cumbria, the centre of Urien’s power, which recalls a “fairy king” called variously Aballo, Eveling, Everling, etc., who has a daughter called Modron. This duo are often linked to local Roman ruins, and there are remains of a Roman fortress near Brugh-by-Sands which the Romans called Aballava, possibly after a local deity or existing placename which may have been linked to the deity.

| illustration of Morgan le Fay by William Henry Margetson | Urien, Owein, and Morfydd are historical persons, while Modron is portrayed as a divinity, or sometimes a “fairy”. The washer-at-the-ford scenario between them cements Urien’s enormous legendary status and possibly a degree of euhemerisation in the eyes of his descendents. It is worth noting that Modron is the instrument used to confirm his status. There are only a few scraps of Modron’s lore left, but they are from enough different sources to indicate that She was at one time an important goddess. However, it’s the washer-at-the-ford story which suggests a role as a sovereignty goddess for Modron, appearing to a young hero-king, coupling with him at a ford, and bearing him twins. And one of those twins is the hero for the next generation, Owein. The scene recalls, although it isn’t identical to, the coupling of The Mórrigan and The Dagda at the River Unshin in The Second Battle of Maige Tuired, and to a lesser extent has echoes of both The Mórrigan and Macha’s relationship to Cú Chulain in the Ulster Cycle. |

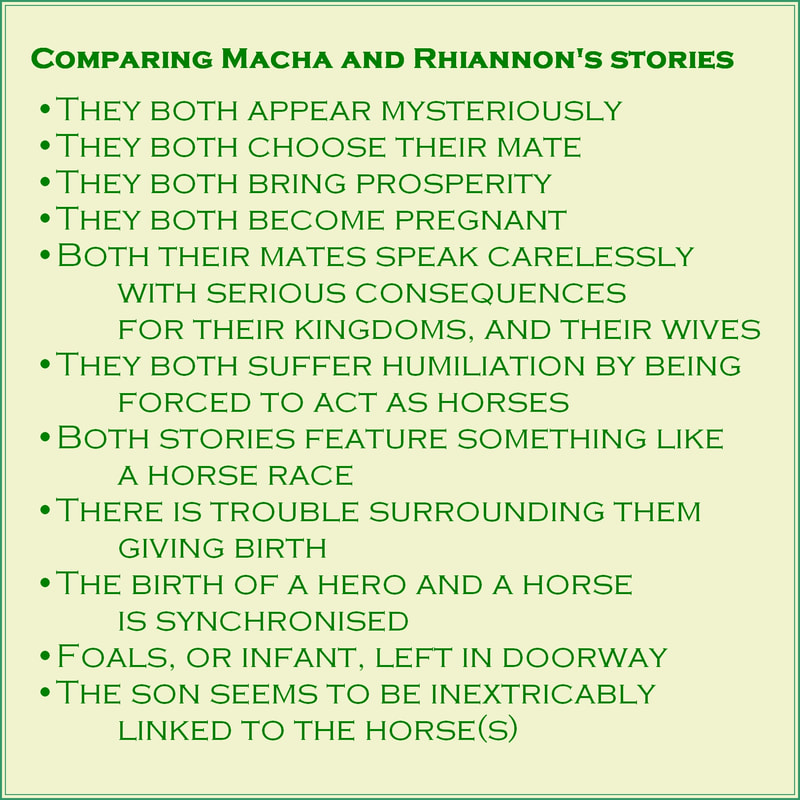

| There are also two links between Rhiannon and The Mórrigan. First, their names. Rhiannon means ‘great, or divine, queen’, and the meaning or Mórrigan is probably also ‘great queen’ (there is some dispute). The second link is through Macha, a goddess who is said to be one part of the Mórrigan’s triple identity. Macha’s story in the Ulster Cycle, which seems on the surface to be very different than the story of Rhiannon, actually has over ten points of similarity to Rhiannon’s story – many of which are not really required to further the plot of either story. I’ve listed these in the text box on the right. The final three on that list refer not to the Debility of the Ulstermen story but to stories of the birth of Cú Chulainn and his two horses. | CLICK TEXT BOX TO ENLARGE |

If you are interested in Arthurian stories, then you may already have picked up on a couple of things. The first writer of an Arthurian saga, Geoffrey of Monmouth, gives the wife of his character, ‘Uriens’, the name ‘Morgan’. Perhaps he didn’t want to give her a name connected with a saint, especially one which in some versions or her story was said to be the daughter of Vortigern. Yet he associates her with the Isle of Apples, or Avalon, which points directly to the story of Modron, daughter of Afallach, in the Welsh material.

Geoffrey’s stories were soon taken up by Chrétien de Troyes, and reworked as French verse. Chrétien also has his Uriens character marrying Morgan la Fay, now cast as the sister of Arthur, and they have as son, Yvain, whose name is obviously based on Owein, so an awareness of Modron’s story is still lurking in the background. Both Chrétien and Thomas Malory portray this Morgan as a supernatural femme fatale.

There is further information about Modron in a video I made called The Goddess Modron; and much of the same information is included as a section in a longer essay on Mabon ap Modron called Who is Mabon? which includes more complete citations.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed