This takes two forms:

1. The Christians wrecked it!

Yes, most medieval texts were copied out in monasteries. As modern people, we tend to assume that if someone entered a monastery, then they must have been almost fanatical in their religious views, but there’s no evidence for this. Sure, if you were a religious fanatic a monastery might be where you ended up, but people were there for all sorts of other reasons. Some were given to the church by their parents as children, some were attracted by the access to books and learning, and it’s quite possible that for others it was seen as a path not that different from becoming a Druid. There is even a line of thinking that some Druids were sort of “underground” in monasteries, although I’m not sure we should take it all that seriously.

Many of the monks were local, or had at least grown up in the culture that preserved the stories which became what we think of as The Mabinogi. It's possible that their main motivation for putting these tales on paper was to preserve them. They believed that the stories had value. I think they were prompted by the same urge to preserve lore that sustained the bards and other lore keepers who had existed for millennia.

There is little, if any, Christianisation of the stories in The Mabinogi. There is some Christianised language salted through the dialogue. This may have just been a reflection of how people spoke at the time, or an effort to put a few “key words” into the text, so that it couldn’t be called completely ungodly. You certainly see this with a lot of early bardic poetry, where most of the Christian references are in the opening few lines, or sometimes the last few lines. As if a nod to Him Upstairs would keep any disapproving bishops off the scent. The stories themselves do not feel like Christian stories – they feel closer to pre-Christian myth.

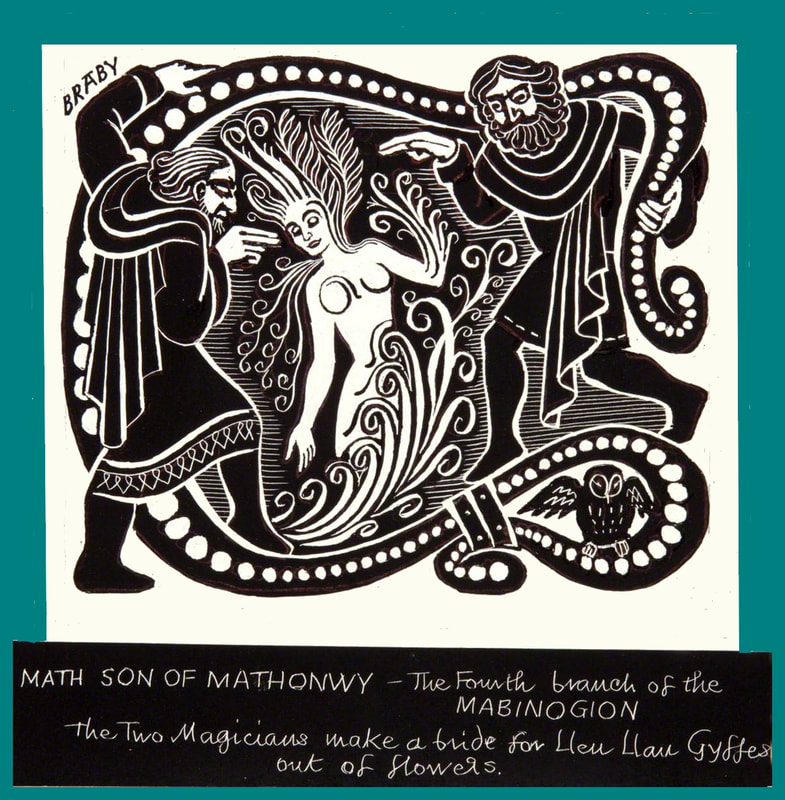

| 2. The jigsaw is incomplete For centuries, there has been an industry devoted to trying to reconstruct “all of Celtic mythology” by drawing on reconstructive linguistics and Indo-European studies. When I look at Celtic myth, I’m impressed by how much we have, rather than upset about what we’ve lost. It’s not that I’m really a “glass half full” sort of person, but when it comes to Celtic myth the glass happens to be overflowing. You could probably never read or know all of the texts that survive. There is plenty enough to be going on with, but look outside if it makes you happier. | Math, Son of Mathonwy - Dorthea Braby (1909-1987) National Museum Wales |

Reading it as fiction

We live in a society that consumes a lot of fiction in the form of books and films. We tend to plough through large books or multi-episode films with an enormous appetite. There’s an analogy there with a glutton stuffing themselves, but not really tasting their food very much.

Medieval texts are usually very economical with words. Some of that came from the need to be economical with ink and vellum, not to mention the human effort required to hand write things. So, The Mabinogi moves very fast. Almost every sentence is meaningful. Major action happens on every page. You can easily read The Four Branches in a day. But can you digest it?

Of course, myth can draw you into all of that, too, but keep your wits about you and you will get more out of it. Rather than wanting to be like one of the characters, or sort of falling in love with a character because you think you have a lot in common, pay attention to what’s going on in the story as a whole and you will find a much more interesting set of layers.

I believe this is good advice:

Take your time. Read a paragraph, think about it, repeat if necessary. Or read a story, sleep on it, or go for a nice walk and think about it. Then read it again.

Get above the trees and look down a the forest. What is going on in the story as a whole? Can you see causes and effects? What’s the cause behind the cause (behind the cause….).

Prepare for ambiguity and deep thinking. There are messages in myths. I believe that there are layers of messages that reveal themselves as we need them. But they are not black and white morality tales. Deep thinking will reveal surprising insights about justice, cosmology, and honourable behaviour. Those insights won’t be simple, or cut and dried. They will be nuanced. Don’t try to reduce them to some kind of Ten Commandments.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed