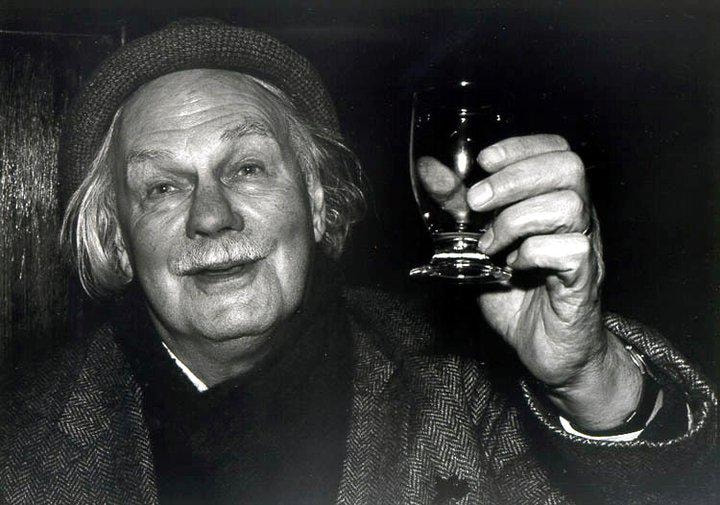

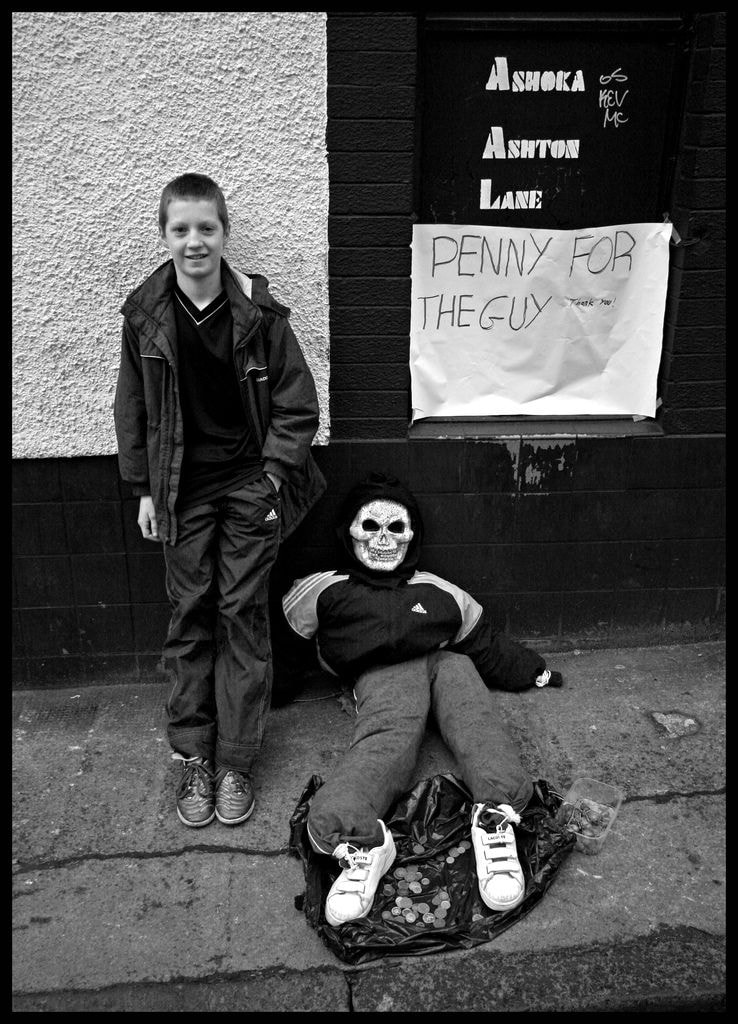

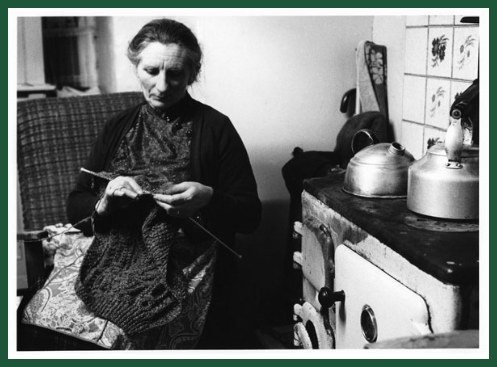

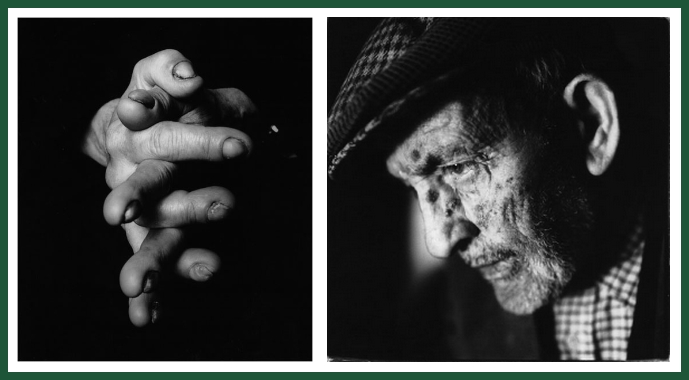

Figures I have looked up to as old men when I was in my thirties and forties are gone now. Poets and tradition bearers, musicians... People close to me have gone, too, several before their time. This is the state of getting older. It's part of the preparation, I suppose.

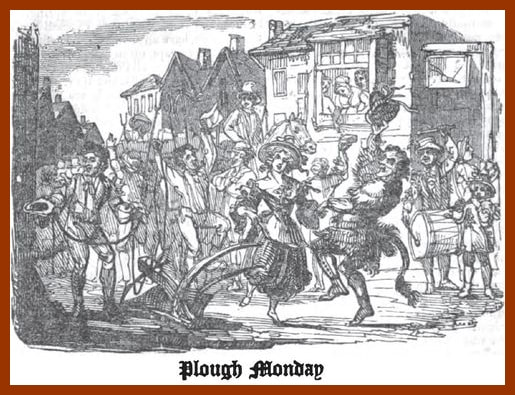

Time sits, I sometimes think, like a moving column of vapour, about any given place. The things that happened there, what was thought or felt, all spirals like some kind of blind spring. The past is immanent, if only imperfectly reachable. I have lived in places where I could sense what the land felt in its waters. Sometimes, it's almost an ecstatic practice. Occasionally, it is excruciating. But I digress.

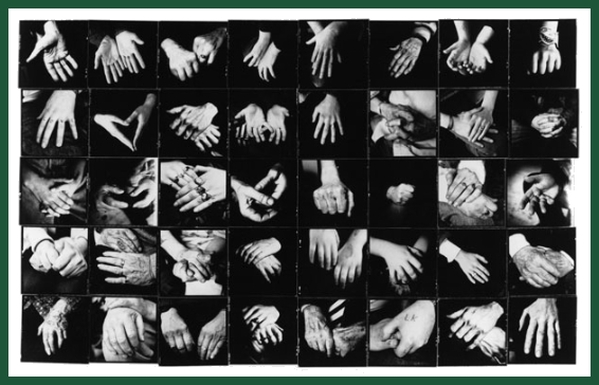

This poem is echoes of times, places and people who have passed. Some well remembered, others only sensed. They now merge and don't merge, spiralling in those columns of vaporous memory above their places. Even the well-remembered past can only live partially in our memories. So much of it belongs to place.

| Lost in Time My elders are becoming my ancestors now. It doesn't happen all at once, or on the day they die. They first must be purified like silver in the fire A process which is not painful, but necessary. Slowly they move from the tumbled houses, Determinedly they step from the photograph pages To build anew that which was lost, That which was gained, but could not be held. Dreamily they drift from their country upbringings And their suburban upbringings among the roses. Drift toward halls of learning and drinking establishments, Smoke filled back rooms of pubs where poets rant.

Aeons and aeons pass, I am becoming the elder, I am becoming the child. I drift toward my elders, I follow the stream of their poesy, A strong stream, through the hills of memory. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed