You can read the stories for yourself. They are in Lady Gregory's Gods and Fighting Men under the heading "Manannán at Play", and in Standish O'Grady's Silva Gadelica as "O'Donnell's Kern". A wonderful, and quite different version from Islay turns up in J. F. Campbell's Popular Tales of the West Highlands as "The Slim, Swarthy Champion." As if that isn't enough, I'm currently working on a retelling of them on my YouTube channel. [Update: Here's the video.]

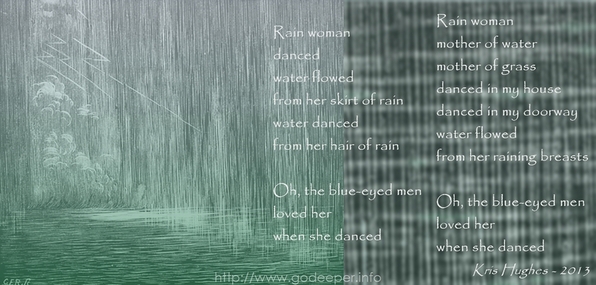

As usual, I have fallen in love with my subject, and as sometimes happens, that led to a poem. It's full of obscure references to the tales, but I will leave you to hunt them down for yourself. You don't even need to leave the comfort of your seat. All those books I mentioned, above, are in the public domain and kicking around on the internet.

I who was hunting with fair Fionn

I who received tribute on Barrule

I who cast off my shimmering cloak

Going about the raths and duns

Paddling from Man to Kintyre

And from Kintyre to green Islay

Rathlin to the seat of Red Hugh

The bodach went seeking crowdie

Hospitality without pride

I never looked for prominence

My tongue was sweet and learned

The voice of my harp beguiling

The son of the earl knew the sweet

The Mac an Iarla knew the sour

From high Knock Áine I vanished

I was a rainstorm on a plain

A healer to the MacEochaid

A cattle raider in Sligo

Until I came to O’Kelly

Twenty marks I got for their taunts

And lulled them into their slumber

With the puddle water leaking

From my shoes I walked to Leinster

Tired I was seeking a mead cup

Their clanging strings offended me

The bloody day they had of me

Bonnyclabber and crab apples

The feast of Manannán mac Lir

RSS Feed

RSS Feed