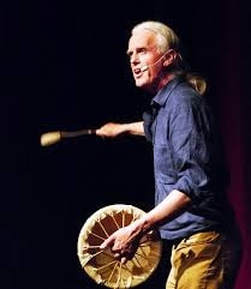

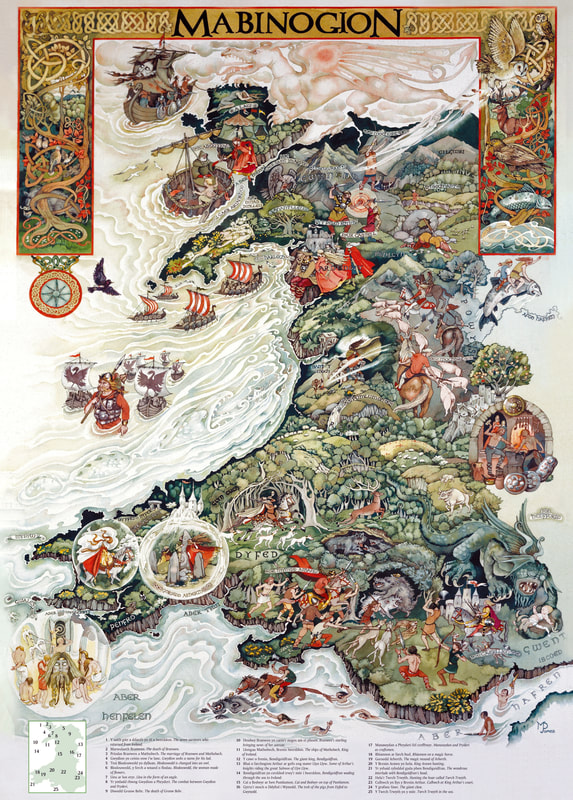

| I've been interested in Hugh Lupton's work ever since I first discovered his poem about the Mari Lwyd. Hugh is an ambitious storyteller (not many will take on re-telling the Iliad or Beowulf), as well as a poet and author, so I was intrigued when I heard that he was writing a book based on the Welsh cycle of stories known as The Four Branches of The Mabinogi. I mostly prefer to read Celtic myths in direct translations, these days, because literary re-tellings leave me confused as to which parts belong to the original text and which to the author. Still, I knew that if anyone had potential to do this well, it would be this man. |

The scribe leaned across the table and whispered into Llywelyn's ear.

"Lord, it concerns Cian Brydydd Mawr."

"What of him?"

He feels the hand of death closing around his heart. His apprentices are dead. Everything he passed on to them, in the old way, with the breath of his mouth, is lost."

"You do not have to tell me. It wounds me every time I think about it."

"Lord, he has made a request. He has drawn me aside and asked that certain matters be set down on the page, matters the will otherwise die with him and be forgotten."

But the Sub-Prior was already standing.

"Lord, if I may speak?"

Llywelyn opened his hand in a gesture of approval.

"Lord, this Matter to be set on the page - it is hardly the province of the Holy Church."

Llywelyn leapt over the high table. The Sub-Prior found himself seized and shaken for the second time.

"How many lands have I gifted to your Cistercian Brotherhood?"

"Many hundreds of acres, Lord."

"And golden vessels, silver plate?"

"You have been most kind."

"And you wish to keep my favour?"

"We do, my Lord."

Llywelyn drew him so close that their noses were touching.

"Then write me my book."

If I could sing I would sing of Bran the Blessed, High King over the Island of the Mighty. |

Mabinogi enthusiasts will enjoy this book, but it would be a perfect gift for someone who enjoys good historical or fantasy fiction, especially if you are trying to spark their interest in The Mabinogi. If you are approaching the four branches for the first time, for study or devotional reasons, I would recommend one of the many excellent translations of these tales instead. However, I think for the general reader who simply likes mythology, or who likes books set in early Britain this book is ideal.

Final analysis. If you are looking for a good read and an easy introduction to The Mabinogi, this is the perfect choice.

| The Assembly of the Severed Head is available to order from the publisher, Propolis Books, and from the usual booksellers. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed