|

|

| ||||

Mabon ap Modron means divine son of the divine mother. We know him from just a few references in Welsh lore. His most significant appearance is in a story called How Culhwch won Olwen, in the Mabinogi. The hero of the tale, Culhwch, is required to do a series of “impossible” tasks, before he can win the woman he loves. One central thing he needs to do is hunt a magical Irish boar called the Twrch Trwth.

It transpires that the boar can only be tracked by a special hunting dog, called Drudwyn, which can only be controlled by Mabon, who was stolen from between his mother and the wall at three days old, and “no one knows where he is, or what he is, or whether he is alive or dead. No-one can ever find Mabon, no-one will know where he is, until Eiddoel his kinsmen, the son of Aer, is found, since he will be tireless in seeking him. He is his cousin." Strangely, Eiddoel is also imprisoned at Gloucester.

There is a long sequence in the story about the seeking of Mabon, which involves asking several very old, wise animals whether they have seen Mabon. This part of the story serves to emphasise the extremely ancient nature of Mabon and his imprisonment. Finally, they speak to the salmon on Llyn Lliw – the oldest of all animals. He tells them that as he swims up the River Severn with the tide, he can hear Mabon lamenting his imprisonment from within the walls of Gloucester castle’s dungeons. Culhwch’s cousin is King Arthur, and Arthur and some of his men free Mabon. He is given a horse called Gwyn Myngddwn (white brown-mane) to ride, and with the hound Drudwyn, Mabon goes on to lead a successful hunt of the Twrch Trwth, and Culhwch gets the Olwen.

What do we learn about Mabon from this? Mabon was stolen in infancy, and imprisoned for a very long time. He might be associated with Gloucester and the Severn. He is a good huntsman and has a way with dogs. The way the story of the search for Mabon is set into the wider tale of Culhwch suggests that it may once have been a story in its own right, possibly with more detail about how he was taken from Modron, or with a pre-Arthurian version of His rescue.

Culhwch and Olwen names a dizzying array of characters, drawn fron deities, legend, history, and probably bardic imagination. Among those mentioned, is Mabon, son of Mellt, who along with a character called Gware Gwallt Euryn (synonymous with Pryderi, another divine prisoner) goes to Brittany to get a pair of hunting dogs. Mellt means lightning, and it is possible that this is an epithet of Mabon ap Modron, a hint at His supernatural nature, or even a statement about his paternity as the son of a god of lightening. It’s impossible to know which of these might be true, but as an interesting aside, there was a Celtic tribe in the Marne region of Gaul known as the Meldi, and it is possible that they had a tutelary deity called Meldius. The movements of the Meldi are poorly understood. The Marne rises at Balesmes-sur-Marne and empties into the River Seine near Paris, but the Meldi had possible territories at some time in places as widely disparate as the Lyon region, Bulgaria and Flanders. There is an inscription at Glanum, near Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, which reads: To Meldius. Silanus son of Lutevus has fulfilled his vow.

A poem in The Black Book of Carmarthen mentions both Mabon ap Modron and Mabon son of Mellt. Pa Gur yv y Porthaur? (Who is the gate-keeper) is a dialogue between Arthur and a porter called Glewlwyd, which features two favourite Celtic motifs: a hero trying to gain admittance to a castle, and a long list of warriors. This translation is from Skene’s The Four Ancient Books of Wales:

Mabon, the son of Modron,

The servant of Uthyr Pendragon;

Cysgaint, the son of Banon;

And Gwyn Godybrion.

Terrible were my servants

Defending their rights.

Manawydan, the son of Llyr,

Deep was his counsel.

Did not Manawyd bring

Perforated shields from Trywruid?

And Mabon, the son of Mellt,

Spotted the grass with blood?

There are a few references, or possible references, to Mabon in other Welsh lore. Triad 52, in the Welsh Triads, lists Mabon as one of the three exalted prisoners of the island of Britain. This translation is by Rachel Bromwich in her Trioedd Ynys Prydein:

Llŷr Half-Speech, who was imprisoned by Euroswydd.

and the second, Mabon ap Modron,

and the third, Gweir son of Geirioedd.

The text of the triad then goes on to say that Arthur is more exalted that these three, and to describe three imprisonments of Arthur.

Another poem from The Book of Taliesin, The Spoils of Annwn, also references a prisoner called Gweir, as well as mentioning Arthur’s boat Prydwen. Gweir, Pryderi, and Mabon may, in some sense, be synonymous. The following passage is translated by Tony Conran in Welsh Verse:

Impeccable prison had Gweir in Caer Siddi,

As the story relates of Pwyll and Pryderi.

Prior to him, there went to it nobody,

To the heavy grey chain that trussed a true laddie.

Because of the spoils of Annwn he sang bitterly,

Three shiploads of Prydwen, we went on that journey.

Seven alone we returned from Caer Siddi.

Finally, we have mention of Mabon in Englynion y Beddau (Stanzas of the Graves), translated here by John K Bollard:

The grave in the upland of Nantlle,

No one knows his remarkable characteristics -

Mabon ap Mydron the Swift.

What have we learned from these? Mabon seems to continue a loose association with Arthur, and possibly gains one with Llŷr and His son, Manawydan fab Llŷr. He is seen as a divine, or exhalted, prisoner. He is also associated with the mysterious Gwier. We’ll consider both of these below.

The title of the collection of tales called the Mabinogi (or Mabinogion) would suggest a connection to the word mabon (son), or perhaps to Mabon ap Modron. There are at least two ways in which this could be true. For the sake of simplicity, let’s just look at the core of the Mabinogi: The Four Branches.

First, mothers and sons. There is much in these tales which concerns mothers and their sons, who are always destined to be kings. In the First Branch, Rhiannon, bears a son to Pwyll. Like Mabon, this lad is stolen from his mother in infancy and missing for a long time. He is at first named Gwri Gwallt Euryn 'Gwri Golden Hair', which some scholars believe bears a connection to Gweir, who is mentioned in two of the poems, above, as being imprisoned. When the boy is returned to his parents, they rename him Pryderi (worry, anxiety).

In the Second Branch, Branwen, daughter of Llŷr, gives birth to a son, Gwern, after marrying Matholwch, the king of Ireland. Branwen is mistreated, and her brother, Brân, leads a disasterous expedition to Ireland to avenge her. While Brân’s warriors are in Ireland, his half-brother, Efnisien, the son of Euroswydd, throws Branwen’s son, Gwern, into a fire, killing him. Only seven men returned alive from this campaign, one of whom is Pryderi. This story is often compared to the Spoils of Annwn, quoted above.

The Third Branch continues the story of Rhiannon. Pryderi has inherited his father’s kingdom and returns from Ireland, accompanied by Manawydan, brother of Brân and Branwen. Rhiannon and Manawydan marry and the group have a series of misadventures in which Pryderi and Rhiannon go missing and are imprisoned in an otherworldly fortress.

The Fourth Branch is a tale of dynastic intrigue featuring new characters. The reigning king is called Math, and he appears to have neither wife nor heirs. However, he has a niece, called Arianrhod, and two nephews, Gwydion and Gilfaethwy. Somehow, probably via trickery on Gwydion’s part, Arianrhod bears twins. One child, Dylan, runs away immediately and swims off in the sea. The other, Lleu, is raised by Gwydion and rejected by Arianrhod, with Gwydion perfoming many machinations in order to put Lleu on the throne. At one point, Gwydion starts a war in which he unfairly kills Pryderi.

Looking at the above, you might draw the conclusion that Pryderi is the mabon (son) after whom the collection of stories is named, or that it is meant to be a collection of tales about mothers and their sons.

Second, tales to instruct the sons of the nobility. The Four Branches, and indeed the other tales in the Mabinogi, offer a wealth of stories about young men making mistakes, and sometimes gaining wisdom, what good and bad leadership looks like, etc. The stories aren’t black and white “morality tales”. They require the reader/listener to think. This has led some commentators to think that their purpose is to teach the boys and young men (mabons). I agree strongly with this idea, but it’s also possible that this use was applied to stories which already existed in the culture for religious reasons.

The Arthurian literature of England and continental Europe drew on characters and stories from the Brythonic speaking culture of pre-Saxon Britain. (Some of this was then re-imported to Wales, where a new mix was created, as in the three Arthurian romances included in the Mabinogi.) So it’s not surprising that we find echoes of Mabon.

In Erec et Enide, the character Mabonagrain is held captive in a garden by his promise to a woman, and spends years missing from the court of Evrain. There he is forced to fight all comers until he is defeated. He overcomes and beheads many knights until he is finally defeated, much to his own relief, by Erec, and is then able to return to court.

In Lanzelet, there is a character called Mabuz, who is associated with a prison because he has one, called the Castle of the Dead, which he fills with knights who he bewitches, causing them to become cowards. In this story, Mabuz is said to be the son of a fairy queen. Modron, discussed below, is undoubtedly the basis for Geoffrey of Monmouth’s “fairy queen” character, Morgan le Fay, in his Vita Merlini, which first popularised Arthurian stories. This helps to confirm Mabuz’s literary relationship to Mabon, but there is no reason to believe that the details of the stories or characters or Mobonagrain and Mabuz reflect Brythonic traditions concerning Mabon/Maponos.

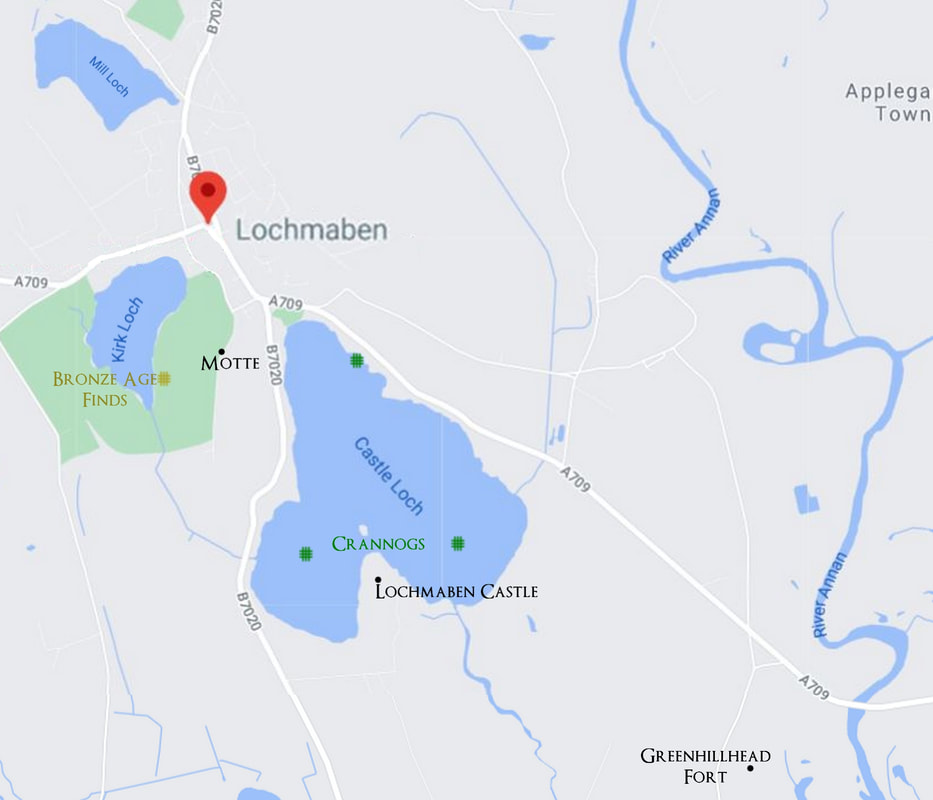

Lochmaben is a small town in southwest Scotland, which is surrounded on three sides by three separate lochs, and on the fourth side by the River Annan. None of these lochs is currently called Loch Mabon, but it is possible that the one known as Castle Loch may have been, at some point in the past. This Loch seems to have been important during the bronze age and early iron age, as it has several possible crannog sites (Canmore 66289, 66316, and 89712) and log boat finds.

| There is a poorly investigated, but scheduled, hillfort just to the southeast of Castle Loch, called Greenhillhead Fort (Canmore 66842) and a medieval motte between Castle Loch and Kirk Loch (Canmore 66314). The visible ruins of a castle (Canmore 66315) which was built and re-built several times between the 13th and 15th centuries could hide earlier ruins, but if so, they haven’t been found, and not much is known about Lochmaben’s pre-Roman history. The castle was used as a seat by the Bruces at times, and by at least one Pictish king before that. So, while Lochmaben is not an important town in modern times, it once had a very high status. | Lochmaben. Click any photo to enlarge. |

There is a traditional ballad, known as The Lochmaben Harper (Child Ballad No. 192), about a harper from Lochmaben who goes over the border into nearby Carlisle to steal a mare from “King Henry”, called The Wanton Brown, having first laid wagers that he could do it. He achieves this by trickery, using his own mare and foal, and by beguiling people, and sending them to sleep with his beautiful harp playing. The story is a comic one, in which the harper gets one over on everybody, making a great deal of money in the process. The ballad exists in both Scots and English language versions, the earliest known date being 1564. It is only of interest here because of the carvings on Apollo-Maponus with a harp, or lyre, on two North British altars. I’m not aware of any other folklore about a harper in the area which might have given rise to the ballad, but it’s an interesting coincidence.

| In 1858, the Ordinance Survey recorded The Clachmabenstane as formerly part of an oval circle of nine stones, with only two remaining. The second stone is still there, incorporated into a nearby fence. In 1982, the stone fell over, and the socket was investigated before it was re-erected. The bottom fill of the pit was found to contain mixed charcoal from oak, willow, and hazel. This was carbon dated with a range of 3500-2850 BCE. Archaeologists conjecture that this may have later been used as a cult centre for Maponos. The location is known to have been used as a meeting place for hearing cases and settling disputes between the English and the Scots in the 16th century. | The Clachmabenstane with fallen stone in foreground. |

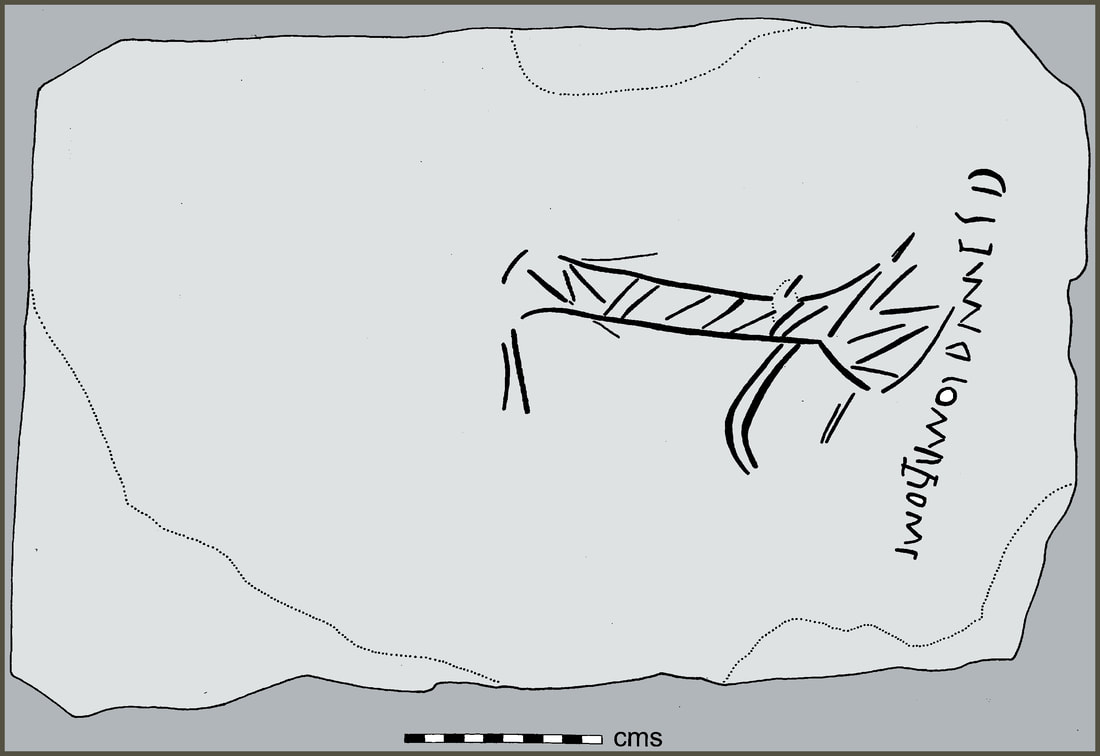

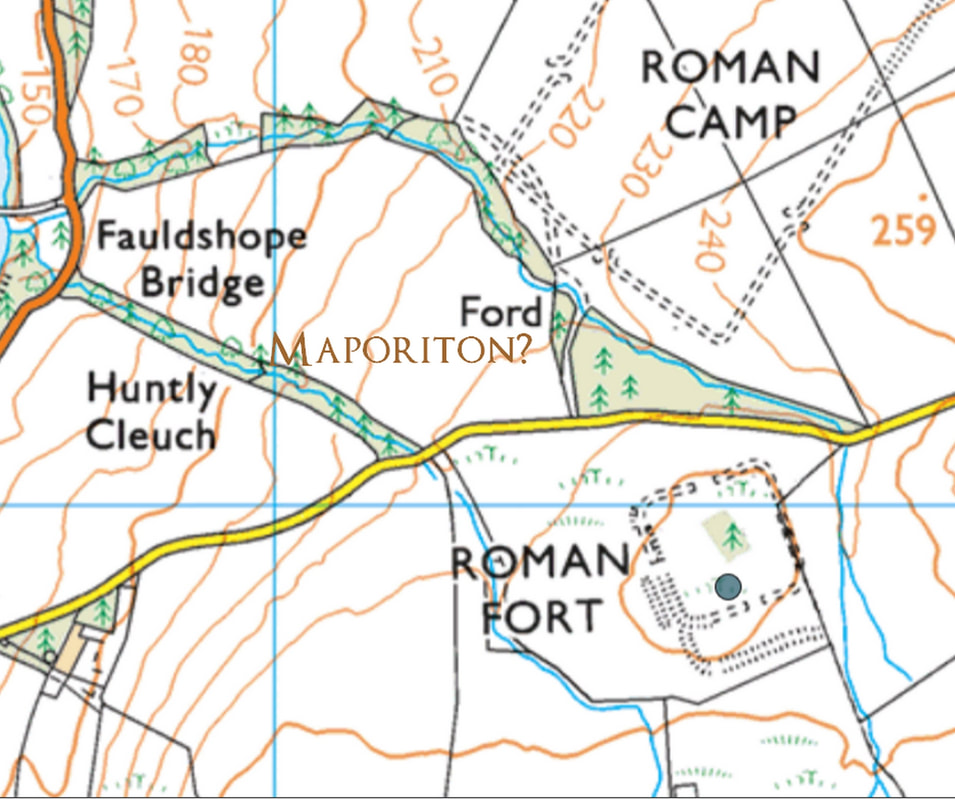

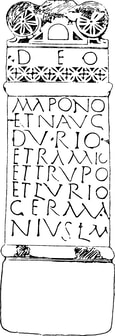

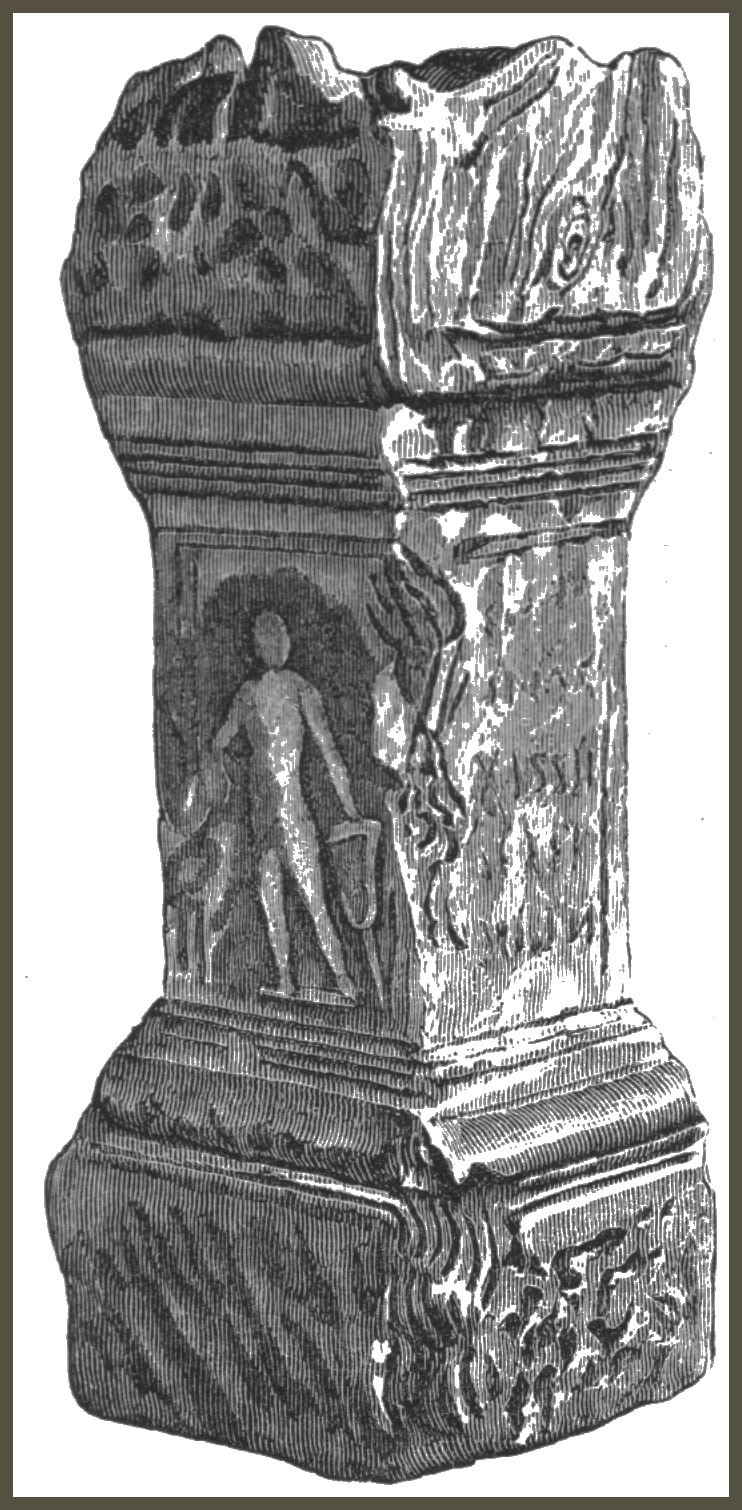

| North British inscriptions to Maponos In 700 CE a place called Locus Maponi was listed in the Ravenna Cosmography. This has long been believed to refer to the Clachmabenstane (or even the town of Lochmaben), but a stone slab discovered in 1963 has created controversy. This slab, (RIB 3482) is thought to belong to the Roman period and was found at surface level in a Roman fort, at a location approximately midway between the town of Lochmaben and the Clachmabenstane. It has a difficult-to-read graffito (informal inscription) and what could be a picture or a dog. There are two tentative readings of the inscription: CISTVM (or CISTAM) DIO MAPOMI, possibly ‘a casket for the god Mapomus’; or alternatively: (donum) Cistumuci lo(co) Mabomi, ‘(gift) of Cistumucus from the Place of Mabomus’ The Ravenna Cosmography also records a place called Maporiton (Ford of Maponos), but like Locus Maponi, discussed above, it’s location is hard to pinpoint. It was at one time thought to be at a small Roman camp, known as Ladyward, just across the River Annan from Lochmaben. More recent scholarship suggests that it is more likely to be at a Roman fort and camp now known as Oakwood (Canmore 54330), about three miles southwest of Selkirk, where there is a ford crossing a stream between the fort and the camp. Continuing along approximately the same south-easterly line from Lochmaben, we come to the area where the only Roman altar (RIB 2063) to Maponus, which does not include Apollo, was found. It is dedicated to “Deo Mapono”. Following Hadrian’s wall east three altars were found at Corbridge, near Hexam. Two of these are dedicated to Apollini Mapono (RIB 1120 and RIB 1121) and one to Mapono Apollini (RIB 1122). The altar designated as RIB 1121 has carved sides – one featuring Apollo with a lyre in one hand and laurel in the other, the other shows Diana with a bow and quiver. At Ribchester, near Blackpool, there is a large stone (RIB 582) with a dedication beginning “To the holy god Apollo Maponus”. Interpreted as part of a monument, rather than an altar, it has a carving of Apollo with a cloak and cap, a quiver on his back (but no bow can be seen). He has a lyre on his right. | Locus Maponi? Ford of Mapono? RIB 482 |

There are several Saint Mabons (also Mabyn, Mabenna), none of whom are well documented, and it is just possible that some of their locations could relate to the earlier deity.

St Mabyn of Cornwall (frequently Saint Mabenna) was said to be one of the many legendary daughters of Brychan, a 5th century king of Brycheiniog, a kingdom in Wales, and is first mentioned in the 12th century Life of St Nectan. She has a church at St Mabon (English: St Mabyn) in Cornwall. There is a 16th century window depicting her in nearby St. Neot’s church, in Loveni. At least one source suggests that this church was actually dedicated to 6th century St Mabon the Confessor, of Y Trallwng (Welshpool). It might seem strange to include a female saint here but it is not unknown for confusion to arise in later centuries about the gender of obscure saints, and there is obvious confusion between this saint and the two male candidates.

Ruabon is the name of a town near Wrecsam, at the northern end of the English/Welsh border. Ruabon means hill, or slope, of Mabon. It has been suggested that this could refer to Saint Mabon the Confessor, or even the Cornish St Mabyn, although the parish church appears to have been dedicated to St Collen until the 13th century, when it became St Mary’s. This St Mabon is said to be the brother of St Llywelyn, both generally referred to as 6th century saints. Bonedd y Seint says they are sons of Tegonwy ap Teon but he is thought to have lived in the 9th century, which would make that relationship impossible.

Another St Mabon is the brother of the more famous St Teilo, with a church at Llanfabon, about two miles northwest of Pontypridd. There is a possibility that the church of Llanvapley, dedicated to an unlikely St Mabli (probably due to a scribal error), could also be associated with this St Mabon. Alex Gibbon writes:

…it would also be significant that a potential church of St. Mabon at Llanfapley stands in close proximity to the church of St. Teilo at neighbouring Llantilio Crossenny – since a St. Mabon site adjoins Llandaf in Cardiff where St. Teilo was said to have become bishop, and it is also suggested by P.C. Bartrum (1993) that the source of an association between St. Mabon and St. Teilo cited by the unreliable scribe Iolo Morganwg (1700’s) is the close proximity of Maenorfabon (St. Mabon) and Maenordeilo (St. Teilo) in Llandeilo Fawr on the Tywi.

There is still a Maes-y-meibon (Mabon’s field) just across the River Tywi from modern day Manordeilo, although any Maenorfabon seems to have slipped from the maps.

Quite close to Manordeilo, at Llansawel, there is a local story of a giant called Mabon Gawr. This is recorded in Peniarth 118, a manuscript dated to about 1600. It contains a long list of Welsh giants and their associated place names. This is from a passage translated by Hugh Owen:

And in the land of Caerfyrddin in Llan Sawel were four giants, and these were four brothers, namely Mabon Gawr, and the place in which this giant dwelt is called to-day by the name of Castell Fabon; and the second … etc.

The passage goes on to list the other three brothers: Dinas Gawr, Chwilein Gawr, and Celgau Gawr, each of whom is given a local Caer with their name attached. This passage probably relates to a folkloric, or bardic, device for explaining the names of ancient forts. There is a “Castell” on the OS map near Llansawel, although it is unnamed.

The Romans conflated their own deities with native deities of lands they invaded and as we see from the inscriptions, above, they paired Maponos with Apollo. Apollo was central to Roman practice and had been adopted from Greek religion without changing his name, unlike most Roman deities. His attributes included athletic and youthful beauty, a connection to hunting and archery (his sister was Diana/Artemis), and a strong link with music, poetry, and dance. Musically, he was particularly connected with the lyre. He was also associated with prophecy. The Delphic oracle was his high priestess. Apollo was also connected with healing, the sun, and water. His healing abilities, however, were such that he was believed to be capable of bringing disease as well as curing it. Apollo had many lovers (not uncommon in Greek myths) but it is probably a mistake to call his a god of love.

The attributes of youthfulness and hunting fit well with what we know of Mabon ap Modron, although it’s far from a perfect fit. There is no mention of healing or disease in Mabon’s story, nor of music and poetry. His imprisonment beside the Severn links him tenuously to water, and some have suggested a link between his imprisonment and release, and the returning sun after the winter solstice. These ideas are interpretations, at best. There is also a possible link between his seeming affinity with dogs and healing, as dogs were among the symbols of healing for both Celts and Romans. Maponos in Gaul has strong ties to healing.

Apollo was also linked with a number of other Celtic deities, including Belenos and Grannus, There are six inscriptions to Apollo scattered along Hadrians wall, plus four in Scotland (two of which are on the Antonine wall), and a further three widely separated over the Midlands. In Wiltshire, not too far from Gloucester and the Severn, there is an inscription to Apollo Cunomaglos (hound lord), which is interesting considering Mabon’s exploits hunting the Twrch Trwth across the Severn in Culhwch and Olwen.

The best-known evidence for Maponos in Gaul is at La Source des Roches (spring of the rocks) in Chamalières, in the Auvergne region of France. An excavation of the area around the spring uncovered thousands of carved, wooden ex-voto offerings, which had been thrown into a pool there. This practice was done to request, or give thanks for, healing. Effigies of limbs, body parts, animals, and male and female figures, purchased from workshops on site, represented the person, animal, or area of the body which required healing. Other types of offerings were also found in the excavation, such as coins, fibulae, and wooden tablets – although no carving is visible on these, so perhaps they were painted. Quantities of hazlenuts were also found, apparently given as offerings.

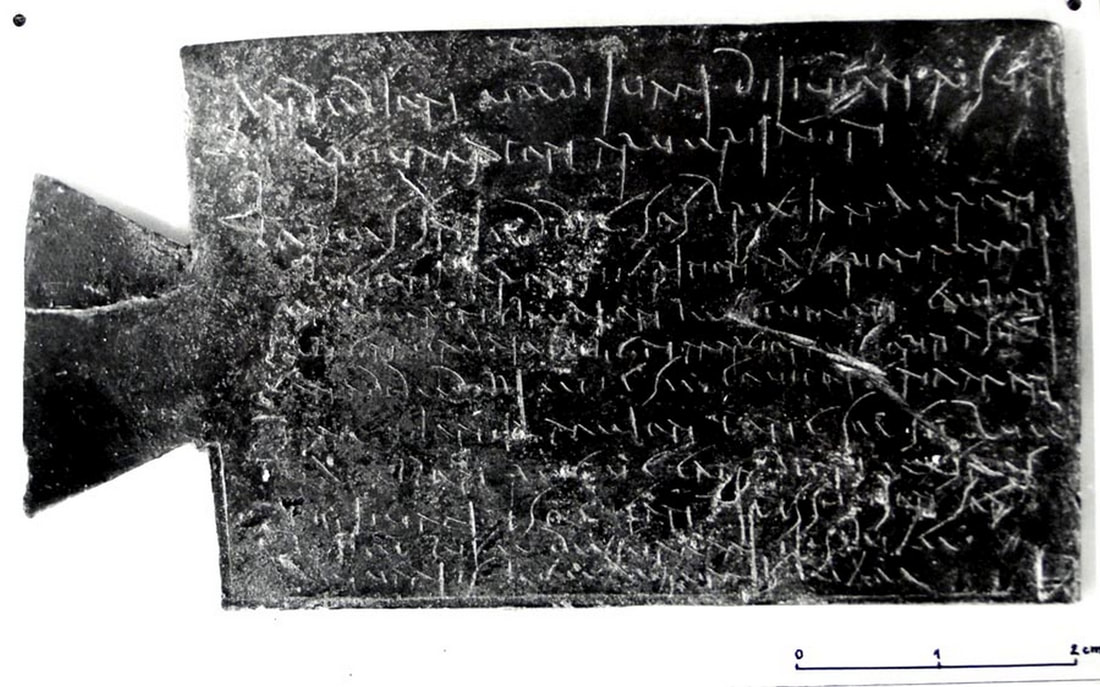

| The Chamalières Tablet | It is a lead tablet found at the site, known as the Tablet of Chamalières, which contains a long inscription in Gaulish addressed to Maponos, written in Latin script. Because it looks similar to “curse tablets” of the period, it was at first assumed to be one, which may have influenced the first attempts at translation. A recent translation by John Koch suggests a request for assistance in a coming dispute or battle. There is, at least, agreement that the inscription is addressed to Maponos. Koch give the opening as: |

It is fair to say that this tablet is the only evidence for Maponos at the Chamalières site, but it seems reasonable that He would have been an important, if not the only, deity being invoked for healing there. This is reinforced by 11th century records of an Abbey at Savigny (Rhône), about 85 miles east of Chamalières, which records a de Mabono fonte. This would be a spring or well associated with Maponos, probably as a holy well of some kind.

The original site at Chamalières was eventually covered by the block of apartments whose building work originally uncovered it. Happily, due to the efforts of a private individual, the spring has been restored, a few metres from where it originally rose.

The famous Coligny calendar also mentions Maponos on the 15th day of Riuos. This may indicate something like a feast day. Although the calendar still lacks an agreed interpretation, some importance was obviously being attached to Maponos.

Finally, at Bourbonne-les-Bains, the site of a thermal spring near the source of the Marne, a funerary inscription mentioning Maponos, as a given name, suggests that his worship was popular in the area. This site is not far from that of the temple of Matrona, mentioned below.

The Welsh texts, folklore, and genealogies, frequently put historical individuals who have achieved legendary status into seeming contact with figures who appear to be deities. This is the case with the great 6th century king, Urien of Rheged, and his son, Owain. In the 15th century manuscript known as Peniarth 50, in the triad known as Triad 70 (The Three Blessed Womb Burdens,) here translated by Rachel Bromwich, we read:

The second, Owain, son of Urien and Mor(fudd) his sister who were carried together in the womb of Modron daughter of Afallach;

It’s an easy calculation for the reader to make, that if Owain’s mother is Modron, that makes him a half-brother to Mabon ap Modron. This is reinforced in an oft-quoted tale from the 16th century Peniarth 147, where folklore tells how Urien meets and couples with a woman washing at a ford, in a scene reminiscent of the meeting of The Dagda and The Morrigan, in The Second Battle of Moytura. The identity of Afallach, as an otherworld king, is also clarified.

"In Denbighshire there is a parish called Llanferres and in that place there is the Rhyd y Gyfarthfa (Ford of Barking). And in ancient times the hounds of the country came together to the edge of that ford to bark. And no one would dare go to see what was there until Urien Rheged came. And when he came to the edge of the ford he saw nothing but a girl washing. And then the hounds stopped barking and Urien Rheged seized the woman and had sex with her.

And then she said "God's blessing on the feet which have brought you here."

"Why?" he said.

"Because a destiny was placed on me to wash here until I begat a son by a Christian. I am the daughter to the King of Annwfn. Come here at the end of the year and you will receive the boy." And so he came and he received there a boy and a girl, namely Owein ab Urien and Morfudd ferch Urien."

In a poem from The Book of Taliesin, about a 6th century cattle raid involving Owain and Urien (Kychwedyl am doddyu o Galchwynydd) the name Mabon is mentioned several times, although it isn’t entirely clear whether it is Mabon the deity, or a mortal warrior with the name Mabon, who is referenced. Some genealogies give Owain a paternal uncle called Mabon ap Idno ap Merchion, in other words, Urien’s brother. Professor John Koch translates the passage like this, in The Celtic Heroic Age:

The manifestation of Mabon from the other-realm

in the battle where Owain fought for the cattle of his country,

A further passage from Koch’s translation reads:

Whoever saw Mabon on his white-flanked ardent steed.

as men mingled contending for Rheged’s cattle,

unless it were by means of wings that they flew,

only as corpses would they go from Mabon.

Of encounter, descent, and onset of battle

in the realm of Mabon, the inexorable chopper;

when Owain fought to defend his father’s cattle,

white-washed shields of waxed hawthorn burst forth.

However, it’s worth noting that a more conservative translation of those first two lines might be something like this one from Lewis and Williams’ The Book of Taliesin:

Mabon was to the fore - Mabon from far away,

When Owain fought - for his land’s stock.

Just as Mabon seems to be a Brythonic continuation of the deity Maponos, the same can probably be said for Modron and Matrona, a goddess associated with the river Marne in east-central France. As well as the obviously cognate name, one can draw a few other connections. The region around the Marne river was the territory of the Meldi, who may relate to the possible epithet Son of Mellt, mentioned above in the section on Culhwch and Olwen.

The only mythical portrayal we have of Modron then, is her occasional mentions as the mother of Mabon, and the two interesting passages quoted above in the section on Owain. Although the Peniarth manuscripts they come from are late in date, it is more difficult to trace the origins of the myth that may lie behind them. That myth might be interpreted as Modron being a river goddess, and the daughter of the otherworldly King Afallach (relating to apples, or land of apples), also described as the king of Annwn. Like the Morrigan in Irish myth, she is found washing at the ford where she couples with a highly important king, who is seen as a great provider and defender of the land. She bears him twins, and the male child goes on to be a great hero.

As the daughter of an otherworld king in these texts, Modron became the starting point for Morgan la Fay in later Arthurian literature. Modron and Afallach are also the source of folklore traceable to at least the 16th century from Ravenglass, in Cumbria, where a Roman ruin is said to be the home of a fairy king called Eveling and his daughter, Modron. In Who Was King Eveling of Ravenglass?, W G Collingwood tends to entange himself in Arthurian literature and spurious genealogies, rather than looking for answers closer to home, but some of his explorations are intriguing, such as:

| Wall of Roman Fort associated locally with King Eveling (Afallach), looking toward Hardknott Pass. | If the Romano-British thought that King Aballo lived at Raven-glass, why was it called Clanoventa (as is now believed) and not Aballava, which as proved by two inscriptions of A.D. 241 and 282 was the name of Papcastle? The nearby Roman fort on the dramatic Hardknott Pass is also considered to be a fortress of Eveling in local lore and, based on its name, Appleby may also be implicated somehow. |

| In the 18th century, a significant Gallo-Roman site was discovered near Balesme-sur-Marne, where the source of the Marne is located. Foundations were found of a twelve room temple complex, with baths, frescoes, and a number of altars, including one dedicated to Matrona. Ex-votos were also found in a nearby cave. It is suggested that Balesme is cognate with Belisama and that she, and Apollo-Belenos, may have been worshipped at the site, which dates to the 1st century. | Source of the River Marne |

Cornwall also has the male Saint Madrun, who has been suggested by John Koch to be connected to the goddess Modron. His holy well, Madron’s Well, near Eglos Madern (English: Madron) in Cornwall, is famous for its healing power, and whether originally Christian or pre-Christian, is of great antiquity. The parish church of the town of Eglos Madern, is called St Maddern’s. It is also dedicated to St Madron, although the existence of an historical St Madron is doubtful.

Áengus Óg (young Áengus) is the son of the god known as An Dagda in Irish myth. An understanding of the etymology of his name, and various versions of that name originating from a variety of Irish texts, and their English translations, will be helpful in understand why he is associated with Mabon. Paraphrasing slightly the excellent explanation given by Dáithí Ó hÓgáin, this is as follows: The name Áengus means “true vigour”. He is also known as Mac ind Óc (modern Irish Óg) but this is ungrammatical in Irish if the genitive “son of youth” was intended. It is, therefore, assumed that this may have been based on a misheard oral source, and that the correct form was either in mac óc or maccan óc, which both mean “young boy” or “young son”.

Ó hÓgáin goes on to suggest that Áengus’ association with “eternal” youth and the warping of time relates, not to the popular modern conception of eternal youth, but to the perception of the young, themselves, that time moves almost imperceptibly and that they will always be young and invincible. This might bear some relationship to the portrayal of Mabon in Culhwch and Olwen, where the seeking of Mabon via animals of great longevity emphasises his seemingly endless youth. Even though he has been imprisoned for a tremendous length of time, he is still seemingly young and vigorous.

I think it is foolish to argue whether Áengus and Mabon are the “same” deity. This is essentially a theological question that will have to remain a matter of opinion. However, their similarities and differences are worth looking at.

Nothing is known of Mabon’s father, beyond the possible reference to Mellt. The Dagda has no discernable association with lightening. However, Áengus’ mother, Boand, is an important, maternal river goddess, like Matrona. She is the goddess of the River Boyne, an extremely significant river in Irish prehistory and myth. The Dagda, himself, flees with the newborn Áengus in order to avoid detection by Boand’s husband, Elcmar, so in that sense he is also taken from his mother in infancy, although there is no mystery as to his whereabouts, nor any mention of imprisonment.

Áengus has several stories that concern romantic love. In Aislingi Óengusai (The Dream of Áengus) he dreams nightly of a beautiful woman until he becomes dangerously lovesick, and eventually they are united, flying off as swans. In Tochmarc Étaíne (The Wooing of Étain), he goes to great lengths to obtain the beautiful Étain for his foster father, Midir. In Tóraíocht Dhiarmada agus Ghráinne (The Pursuit of Dermaid and Gráinne) he does all he can to protect the lovers as they flee from the wrath of Fionn.

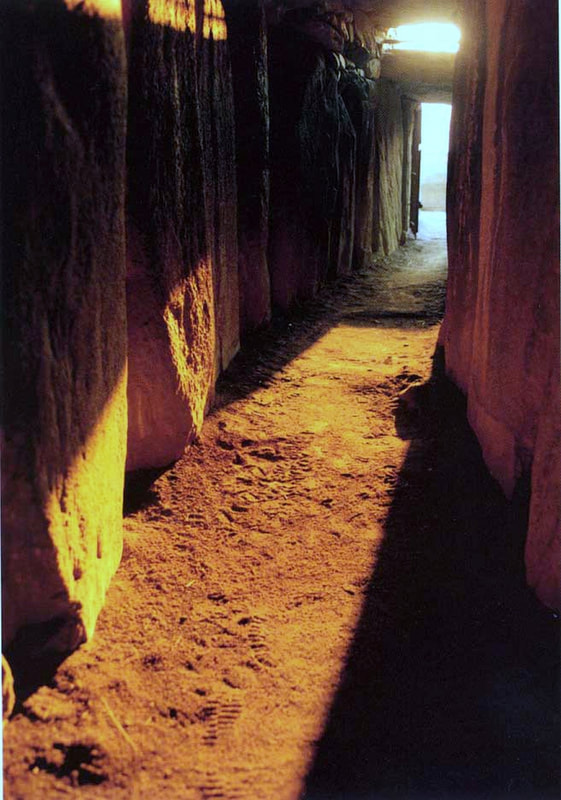

| In Cath Maighe Tuireadh (The Second Battle of Moytura), however, we find a clever Áengus advising his father on a plan to rid himself of an annoying co-worker while bringing the unwholesome king, Bres, into disrepute. In Tochmarc Étaíne he carries out a plan to trick Elcmar out of his home, The Brug na Bóinne (Newgrange) on the advice of An Dagda. Both this story, and the story of Áengus’ conception, involve trickery concerning time, which John Waddell, and others, have suggested may relate to the winter solstice alignment of the Newgrange monument. In other references to Áengus in Irish texts, he is referred to as a great warrior, as are most members of the Tuatha Dé Danann. | Illumination of the passage at Newgrange at the winter solstice. |

This is not an exhaustive exploration of stories concerning Áengus but is intended to cover enough examples to give a fair overview of his attributes and associations. While Áengus has a great deal of mythology to draw on, Mabon has little that survives, and Maponos has none. Due to this situation it can always be argued that Mabon and Maponos might have myths which parallel those of Áengus.

Before we consider this, it might be useful to look briefly at the work of W J Gruffydd concerning The Mabinogi. Although these were scholarly explorations not, I think, intended to be applied to religion or spirituality, they had an influence on early 20th century Pagan and Druidical thinking.

Gruffydd’s starting point was that Welsh mythology was badly fragmented, with many tales lost, and others obscured by Medieval editors. His viewed the situation as a jigsaw with half the pieces missing, and his work attempted to reconstruct the overarching themes of that mythos. This view still informs the approach of modern polytheistic reconstructionists.

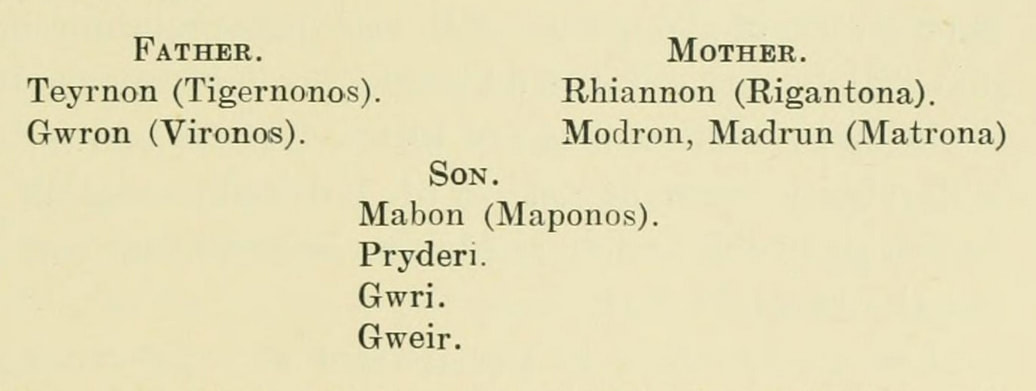

Perhaps the most influential of Gruffydd’s ideas, as far as neopagan thinking is concerned, was his theory of a divine family, consisting of a mother and father goddess (or king and queen) and their divine son, and an idea that these roles might be taken up by different deities at different times. (See below.) It is worth noting, however, that Gruffydd was critical of Sir James Frazer’s “cultural” approach to similar material, and its influence on the work of Sir John Rhŷs.

Where Mabon ap Modron is concerned, these ideas were thoroughly developed by Caitlin Matthews in her book Mabon and The Guardians of Celtic Britain. Her system involved an ever-rotating series of three roles:

Mabon, the Wondrous Youth, the Pendragon’s champion, who succeeds to the place of . . .

Pendragon, the King, the arbiter and ruler, who succeeds to the place of . . .

Pen Annwfn, Lord of the Underworld, the judge and sage, who succeeds to the place of . . . Mabon

Matthews’ scholarship is good, but projects the concept of archetypes begun by others, onto the texts of the Mabinogi, rather than treating Mabon, Rhiannon, etc. as deities. Instead, they become symbols for the use of those seeking to gain enlightenment.

Ross Nichols, the founder of OBOD associated a “child of light” with the winter solstice, celebrated in OBOD as Alban Arthan (The Light of Arthur) He writes:

Born is the Sun God as a dependant infant – who in some mysterious way has managed to escape the powers of darkness seeking to destroy him while he was still in the cradle of Winter.

While Nichols doesn’t mention the name Mabon in this passage, it is a clearly developed idea in later OBOD literature, that this Sun God is “The Mabon”. In a discussion of the winter solstice which later references Jesus, Newgrange, and Mithras we read:

Arthur is equated with the Sun-God who dies and is reborn as the Celtic ‘Son of Light’ – the Mabon – at the Winter Solstice. It is Arthur who will be reborn – awakening from his slumbers in a secret cave in the Welsh mountains, to return as Saviour of the British Isles.

While the Mathews’ and OBOD’s approaches no doubt have the most sincere intentions, from a 21st century perspective it is easy to get a sense that cultures are being mined for handy symbols, in an attempt to create a new, universalist sprituality, which is as unrecognisable to the people of Wales who grew up with tales from Y Mabinogi, as it would be to devotees of Maponos in the 1st century.

A more problematic, and perhaps less respectful, appropriation of Mabon occurred in the 1970s when Aiden Kelly decided to rename the neopagan celebration of the autumn equinox “Mabon”. Kelly has explained how this came about:

It offended my aesthetic sensibilities that there seemed to be no Pagan names for the summer solstice or the fall equinox equivalent to Ostara or Beltane—so I decided to supply them. … Still trying to find a name for it, I began wondering if there had been a myth similar to that of Kore in a Celtic culture. There was nothing very similar in the Gaelic literature, but there was in the Welsh, in the Mabinogion collection, the story of Mabon ap Modron (which translates as “Son of the Mother,” just as Kore simply meant “girl”), whom Gwydion rescues from the underworld, much as Theseus rescued Helen.

The thing that is probably most objectionable about these three uses of the god, or name, Mabon, to modern polytheists is the way they tend to obscure the historical or mythological identity of the deity. If cultural appropriation seems to strong a word, then insensitivity surely is not.

With the advent of neopagan polytheism, there is a small, but growing body of people honouring Mabon and Maponos through prayers, offerings, and other acts of devotion. This group usually have a good awareness of the myths and historical background associated with them, and perhaps take an interest in some of the sites which are associated with the two divine sons, and their two divine mothers.

Far from being obscure deities, there is good evidence that the worship of Mabon and Maponos was important and widespread in Gaul and North Britain in the first centuries BCE. A look at the map of Britain showing associated sited (above) gives a good indication of the special importance of Mabon and Maponos in northern and western Britain. The culture of Gaul and Britain suffered a great deal of stress due to Roman genocide, invasion, and colonisation, followed by several centuries of war with Germanic invaders. It is therefore not surprising that by the time the mythology embodied in The Mabinogi, was finally written down, after a thousand years of Christianisation, much was unclear. However, it is to the great credit of the Britons, especially the Welsh bards, that so much survived, including some understanding of Mabon ap Modron.

Baring-Gould, S. The Lives of the Saints, Volume 16. London: John C. Nimmo, 1898. p. 276.

Bartrum, Peter. A Welsh Classical Dictionary: Peope in History and Legend up to about A.D. 1000. Aberystwyth: National Library of Wales, 1998. (digital publication)

Beck, Noemie. Goddesses in Celtic Religion Université Lyon 2, 2009. pp. 388-391.

Bollard, John K. ed. and trans., and Anthony Griffiths, photographer. Englynion y Beddau: The Stanzas of the Graves. Llanrwst: Gwasg Carreg Gwalch, 2015. p 58.

Bromwich, Rachel. Trioedd Ynys Prydein. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1961. pp. 40-143, 185-186, 433-436.

Collingwood, W. G, Who was King Eveling of Ravenglass?. in the journal Transactions of the Cumberland & Westmorland Antiquarian & Archaeological Society Vol 24, 1924. pp. 256-259.

Conran, Tony. Welsh Verse. Bridgend: Seren Books, 1967. p. 133.

Fitzpatrick-Matthews, Keith. Britannia in the Ravenna Cosmography, A Reassessment (Revised 2020). Retrieved from: academia.edu/4175080 pp. 46-47, 79-81.

Gruffydd, W J. Mabon ap Modron in the journal Y Cymmrodor, Volume 42. London, 1931. pp. 140-147.

Gruffydd, W J. Rhiannon. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1953. p. 100-101.

Koch, John and Carey, John (eds.) The Celtic Heroic Age. Aberystwyth: Celtic Studies Publications, 2003. pp. 368-372.

Lewis, Gwyneth and Williams, Rowan. The Book of Taliesin. London: Penguin Classics, 2019. pp. 134-136.

Mackenzie, Donald A. Wonder Tales from Scottish Myth and Legend. Glasgow: Blackie and Sons, 1917. pp. 22-32.

Matthews, Caitlin. Mabon and The Guardians of Celtic Britain. Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions, 2002. (revised from 1987) pp. 20.

Ó hÓgáin, Dáithí. The Lore of Ireland. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press, 2006. pp. 20-23.

Olding, F. The Gods of Gwent: Iron Age and Romano-British Deities in south-east

Wales The Monmouthshire Antiquary 35, 2019. p. 25-30.

Order of Bards, Ovates, and Druids publication: Alban Arthan. Lewes, East Sussex, 2001. pp. 2-3.

Owen, Hugh. Peniarth Ms. 118, fos. 829-837 in the journal Y Cymmrodor, Volume 27. London: 1917.p. 133.

Skene, William F. The Four Ancient Books of Wales Volume 1. Edinburgh: Edminston and Douglas, 1868. p. 262.

Vanbrabant, Luc. About the Meldi in Western Europe. Retrieved from: academia.edu/43871064

Waddell, John. Archaeology and Celtic Myth. Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2015. pp. 18-25.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed