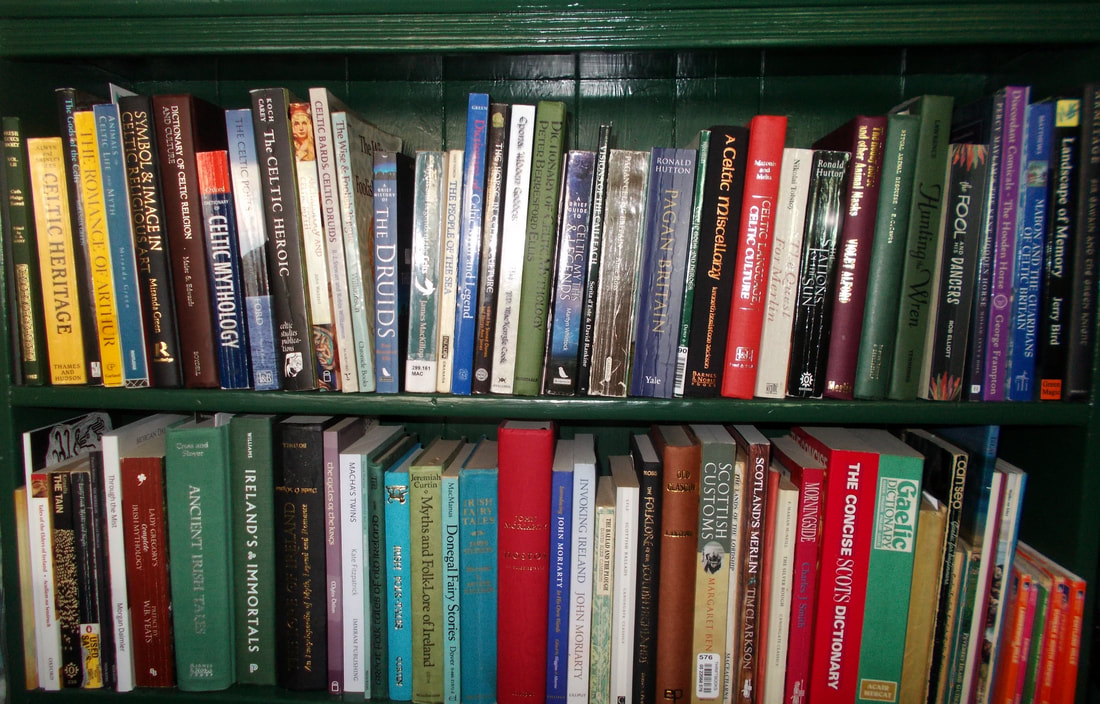

I think this follows on pretty logically from what I was saying in a recent post about people buying up Celtic Studies books and not using them. It reminded me of why this happens, because I know people buy them with good intentions. I often recommend what I see as reference books, but people are trying to read them cover-to-cover.

If you’re interested in Celtic myth and related things, then ultimately the goal is to join up what you learn in one book with what you’ve learned from other books you’ve read. Some books are meant to be read cover-to-cover. That’s obviously the best way to read fiction. It also works really well for non-fiction books with a more-or-less linear narrative structure. Books on history for example, or any topic in which the author is building up a picture – starting with background material, building up layers of knowledge and presenting theories, tying things together in the final chapter.

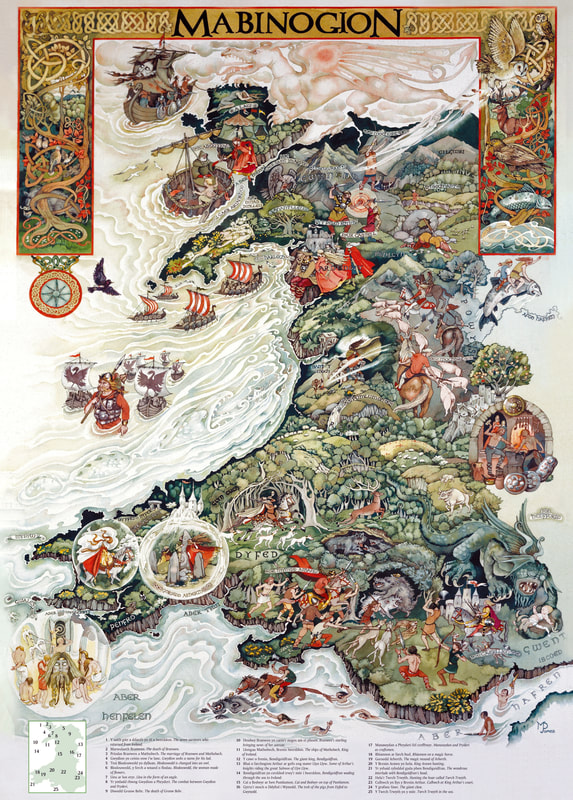

The two books mentioned above are about mythology, but books of mythology are usually collections. I’m thinking of things like Cross and Slover’s Ancient Irish Tales or Koch and Carey’s The Celtic Heroic Age. Many of us like big books. We’re used to reading modern fictional trilogies, for example. But mythology doesn’t read like fiction. It rarely spends much time on what the characters are thinking, or even on description. The narratives are often concise, sometimes downright terse. A lot can happen in a sentence or a paragraph, and you need to adjust the pace of your reading to make the most of such texts. Slow down and give yourself time to picture the details of scenes, consider the motivations and possible emotions of characters, and so on. (There are exceptions. The Tain, or Culhwch and Olwen, for example, are very wordy in places.)

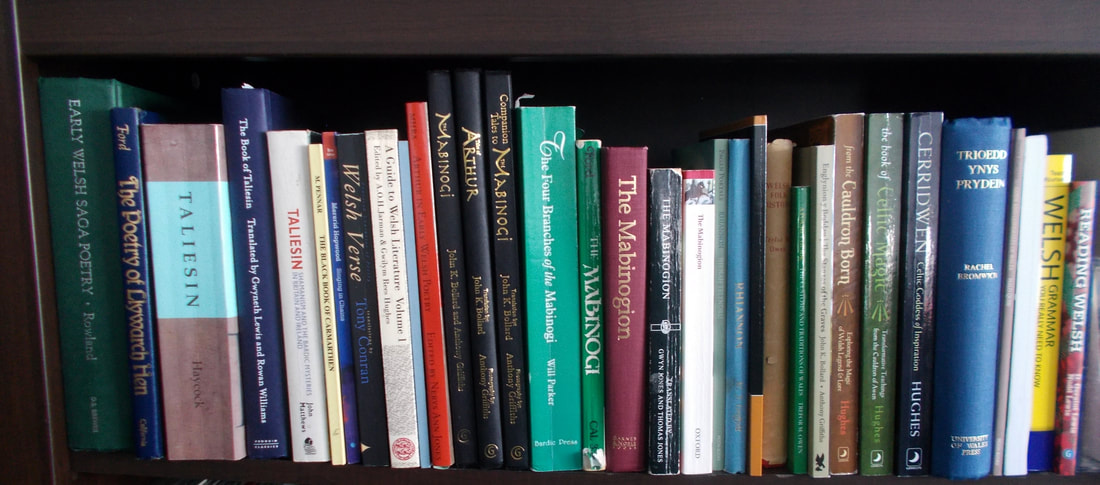

Another book which came up was the Legendary Poems from the Book of Taliesin by Marged Haycock. This is an excellent scholarly translation of a very difficult collection of poems. I love this book, but I can’t imagine most people getting much joy from reading it straight through. Or, at least not unless you go slowly. You could spend a couple of days on the introduction. It's not that long, but if you’re new to the subject it’s still quite a bit to take in.

Each of the poems has a lengthy headnote which is worth reading. Each poem also has many footnotes. Most of these discuss why Haycock translated a word or line the way she did, and possible alternatives. They’re pretty interesting to me – maybe not to you. It’s enriching to read them and perfectly okay to ignore them. Honestly, I’d say one poem a day is enough with this book. Read it thoroughly, read the notes, do it justice. Sleep on it, or go read something a bit lighter. I generally go to this book because I'm reading something which mentions one of the poems, and then I want to go deeper into it.

If you want to read the poetry of Taliesin in a more relaxed but slightly less scholarly format, you might like Lewis and Williams’ The Book of Taliesin, which is another modern, still quite scholarly, translation. It offers you enough information to help you make sense of things, but is more manageable.

Obviously, I can’t talk about ALL the books here! There are lists everywhere of “the best books to read” about Celtic myth or history. Unfortunately, such lists rarely tell you what the book is like, what it’s for, or how to get the most out of it. If you’re asking people who are more knowledgeable than you for book recommendations, it’s helpful if you tell them what, specifically, you want to learn. You want stories. You want the history of ancient Scotland. You want a good dictionary of Celtic mythology. Whatever. There is also no shame is saying, “I got myself a copy of ___ but it’s not making much sense. What am I supposed to use it for?”

You could even ask me in the comments!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed