For whatever reason, I never bothered too much about this. As a kid, I knew I was adopted, and from a young age I had a nerdy fascination with Scotland specifically, and the British Isles generally, which had nothing to do with adopted heritage. I just felt it, and it was strong. I grew up in the sixties and seventies, a time when British culture was cool thanks to The Beatles and British fashion, and much that went after, from the popularity of JRR Tolkein to the Irish music boom. This possibly made my preoccupation seem less odd than if might have in another era.

I ended up moving to Scotland, where I made my living playing and teaching traditional Scottish music. I seemed to rather effortlessly go native for the next 25 years of my life. Much of that time had a "pinch me in case I'm dreaming" quality for me, as I seemed to increasingly become the person I had always known I was.

My experience in Scotland was one of being almost universally accepted and welcomed. One of my fondest memories is of being at a folk club one evening not long after I arrived. I'd played a few tunes, and one of the elder women of the Edinburgh folk scene had come over for a chat with me later. My American-ness came up, and I said something about feeling very at home in Edinburgh already. Her response was, "Juist because ye're born in a stable, disnae mak ye a horse." That simple. You feel comfortable here. We feel comfortable having you here. It's all good.

I have occasionally wondered whether I was really of Scottish ancestry, or just felt like I was. I knew that my biological father's surname was Allan, so it's possible. Or at least some UK ancestry is likely. I never wanted to know who I was, genetically, badly enough to try to find out my history. My adoptive family had not instilled a strong sense of family ties in me, and my relationship with my adoptive mother hadn't been a good one, so I was ambivalent about families generally. At the same time, I felt very secure in my identity as a Scot, albeit an adopted one. In fact, I possibly didn't realize just how Scottish I felt until I came back to the US to live.

Then, about a year ago, my biological sister, who I never knew about, contacted me. This was shortly before the period I refer to as "when all hell broke loose". (In case you missed it,"hell" included my partner dying suddenly, losing my job, having to sell my farm, being on crutches for months, and re-locating across several large western states - all with very little support.) Because of all that, the appearance of my sister, Shanna, has been something I'm only just beginning to process. We had a very nice visit together last month, and feel a kind of bond, but of course we struggle with not having any shared history, since we were both adopted in infancy.

When Shanna came to understand my bond with Scotland she got excited on my behalf. We have Scottish heritage, as they call it. Our mutual mother's maiden name was Sandlin, which is a shortened version of the Scottish name Sandilands. So there you have it - I'm officially Scottish. Well....

This knowledge briefly shook me in some core place. I eagerly read the history of the Sandilands, and discovered that the head of that small clan currently resides in the family seat, Calder House, in West Lothian - within spitting distance of Edinburgh, where I lived for most of my adult life. I've played gigs and ridden horses all over the Calders. So what?

That's what I found myself thinking. So what? What has changed? Has anything changed? I don't know. Shall I nip over to Mid Calder and chap the door, and let them know I'm found? Probably not. What I'm really left with is a very thin line, that has grown thinner with each generation. A line made up of men, who all happened to have a father called Sandilands (until one of them decided Sandlin was simpler). Men who, for all I know, may have been largely indifferent to their women folk. Where would I end up if I traced the maternal line of my mother, my grandmother, her grandmother back, not via their married names, but their maiden names? But of course a maiden name isn't taken from the mother, either. Our matrilineal heritage has been taken from us by the custom of marriage. By the drudgery and depression so many women experienced, which meant that they didn't bother to tell their daughters who their grandmothers and great grandmothers were. By the eagerness to marry and move out into the world that meant that even if they did, the daughters were only half listening. That feels a little sad, but it's our normal.

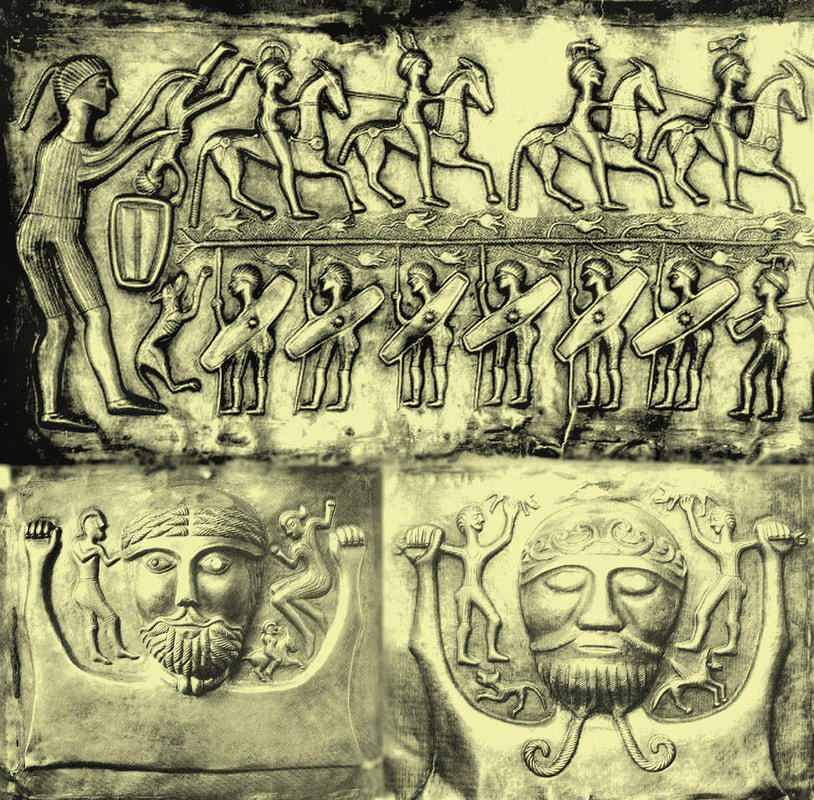

Recently, I've been putting together material in preparation for doing a little informal teaching of Celtic Studies. Today, I was thinking about the gods - of Gaul, and Britain, and Ireland. Their parentage is also all mixed up. Maybe it was once kept in good order by the Druids, we don't know. But if it was, history eventually erased much of it. The myths detail the parentage of some, but it is confused. Like family trees, names get recycled, individuals get confused, change their names, or just drop out of sight. Almost everyone seems to have a foster mother, or foster father. I wonder. Was that a cover story for the family records being in such poor order by the time the medieval scribes tried to write it all down into bestsellers like The Book of Invasions and The Mabinogi? Or was that just the Celtic way? It seems that at least equal emphasis was put on what kind of horse you were raised to be, as which stable you were born in.

It's popular these days, among some neo-Pagan polytheists, to feel that the Gauls or Irish or Welsh were the only true Celts, or that their own heritage and DNA gives them a rightful place in the revival of Celtic religion. But the ancient world of the Celts seems to have been like one of those cauldrons they were so fond of. Not so much a melting pot, perhaps, as a mixing pot. A pot of plenty that never got tired of producing another tribe, a new twist on the language, a new homeland or a bunch of new old gods. A cauldron that could bring forth not only whatever one desired to eat and drink, but also whatever identity made sense in the place one found oneself.

When I found out about my bit of Scottish ancestry, I can't say I was at all surprised. That's not to say that it is without meaning to me. I feel a new warmth when I mention my ancestors of kin in my morning devotions. But I felt perfectly secure in my place as a Scot already. That country welcomed and fostered me for a very long time. I'm not sure whether blood proves anything further.

As my new clan motto says: Spero meliora (I hope for better things).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed