According to old Irish texts, Lughnasadh was instituted by the god Lugh to honour his foster mother, Tailtiu, who died clearing land for agriculture. The agricultural aspect, particularly harvesting grain, would make sense for a festival at this time of year. Lughnasadh/Lammas was a time of important agricultural fairs all over Britain and Ireland until the mid-20th century. Once the grain was harvested, rents had to be paid, agricultural workers might look for a new position, marriage bargains were often struck, and people were looking for a bit of fun, too.

In Ireland, Lughnasadh fairs, or óenacha, might also include athletic games or horse racing. Two of the most famous of these fairs were held at Emain Macha, near Armagh, in Ulster, and at Teltown, County Meath. The fair at Teltown (Irish Tailtin) is the one said to have been instituted by Lugh in honour of Tailtiu.

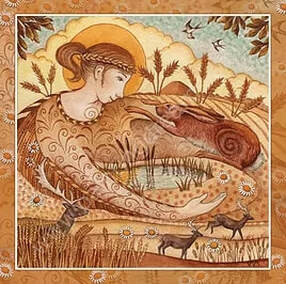

| Tailtiu is portrayed in Irish myth as daughter of the king of Spain, whose name is given as Mag Mor (Great Plain). She is married to the exemplary Eochaid mac Erc, king of the third wave of settlers in Ireland, who were known as the Fir Bolg. After the Fir Bolg were defeated by the Tuatha Dé Danann, Tailtiu paired with one of their number, and in time was given Lugh to foster, by his father, Cian, also of the Tuatha Dé Danann. Lugh’s true mother was Eithne, daughter of Balor of the Fomorian race, who was an arch-nemesis of the Tuatha Dé Danann. It appears that the Fir Bolg never went to war against the Fomorians, so Tailtiu would have been an ideal choice to protect the child, as well as being of noble rank. |

According to the Rennes Dindshenchas, “Their mother died of grief here in her hostageship, and she asked the Tuatha Dé Danann to hold her fair at her burial-place, and that the fair and the place should always bear her name. And the Tuatha Dé Danann performed this so

long as they were in Erin.”

The story of Macha Mong Ruadh (red-haired Macha), daughter of Aed Ruadh, is also given as a reason for the naming of Emain Macha. This Macha won and held the kingship she inherited from her father, variously killing, marrying, and enslaving those who opposed her rule. It was said that she forced the cousins she enslaved to build Emain Macha.

| So, we come to Macha, wife of Cruinniuc. This is the Macha who appeared mysteriously at the home of Cruinniuc, a wealthy widower and cattle-lord, and without a word took over the duties of wife and housekeeper. Her presence brought prosperity, and in time she fell pregnant. One day, Cruinniuc decided to attend a fair. Macha told him not to mention her to anyone while he was there, but before long he had carelessly boasted that his wife could outrun the king’s horses. The king was angered, and Macha was brought to the fair and forced to prove her husband’s claim in order to save his life. Macha felt her labour pains starting and asked to be allowed to give birth with dignity before she ran, but the king and his assembled men refused. The race began and Macha won, giving birth to twins as she crossed the finish line. She then cursed the men of Ulster, that they would be helpless and feel the labour pains of a woman whenever they were required to do battle. This, as I mentioned above, had grave implications in The Tain. |

Another name for Lughnasadh is Brón Trogain, which means something like “sorrow of the earth” and includes implications of the pain of giving birth. In each of these stories I have shared, we see sovereignty goddesses ending their time in pain, sorrow, or bondage. As hostages. As work horses. What is the real message of these tales for us today? I can’t help feeling that we are too quick to apply a story of almost Christ-like sacrifice to these goddesses of the land, who die in pain and grief so that the people can eat. Are we okay with sacrificing women’s sovereignty, nature’s sovereignty, for this? Or should we be reading these myths as cautionary tales?

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

- A Dream of Lughnasadh - Morgan Daimler

- The Victory of Lugh - Blackbird Hollins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed