| | I am looking forward passionately to teaching this upcoming course about the beautiful Celtic gods and goddesses, and their mystical, magical stories. I wanted to write something, to say how much I love them - the deities and their stories. Well, this is that something. The teaching, of course, will be more coherent. |

| If I begin, it will be with Brigid. Did my journey start with Her? Saint or goddess, Bride, or Brighid, or Bridget – for all Her wide appeal, She’s a slippery one. Hardly featuring in the old texts at all, She has only the faintest of mythology as a goddess. Much more as Saint Brigid of Kildare, of course. (There are fourteen other St. Brigids in Ireland– but never mind!) Shall we speak of Brigando, and Brigantia? Shall we return to the keening mother of Ruadhán, to the goddess of poetry and smithcraft? Goddess-saint of healing wells. |

Lugh, who was once Lugos in Gaul and Iberia, but it is in Ireland that His story is so rich. Hero, foster-son. Son of both the Tuatha De Danann and the Fomorians. Lugh, who killed his own grandfather in battle. The many-skilled one, leader of a skilled people. He returned to father Cú Chulainn in a dream, and returned again to confirm the sovereignty of Conn of the Hundred Battles. Or so they say. He may somehow be Lleu. Their stories are different but nothing is impossible here.

These were the first deities I knew, and they were hard to know, partly because I had no point of reference. No sense of how or where to read their stories or not-stories, I went forward, mostly blindly, for years. It’s a wonder I didn’t lose interest completely, but even the thread of their names, an occasional sense of their presence was something.

They are woven gently through the landscape of their homelands. Don’t only look for them in the stone circles and under dolmens – you can find them all over. Go to any path that follows running water. Between two hills with beautiful curves, or in a hazel copse. Tread the same path repeatedly, and the very energy raised by your footsteps will awaken them. Or so it was for me.

These are the gods who went into the hollow hills. They receded into the very atoms of the hollows of nature. They are in the here-not-here. They are right beside you.

I began to find their stories. Mostly the tangled web of Irish stories, and from this emerged Manannán mac Lir, the beautiful, wise, generous god of the sea. He may be named for the Isle of Man or the island may be named for Him. He must, somehow, be one with Manawydan fab Llyr – son of Beli Mawr, second husband of Rhiannon. It’s just that we don’t know how they are one.

Do not enter the realm of the Celtic gods if you want black and white answers. There are no certainties here. They are mist. They are sunbeams. They will not get their stories straight in order to reassure you. It’s all hide and seek through a maze of texts, manuscripts, and recensions. Genealogies that go in circles, and cognates that don’t quite work. Ducks that don’t walk like ducks, and swans that may be princesses.

Don’t get me wrong. Scholarship is rewarding here. Just temper it with patience, and with mysticism. Allow imagination. Give it all time. You can’t know it quickly, no matter how high an achiever you think you are.

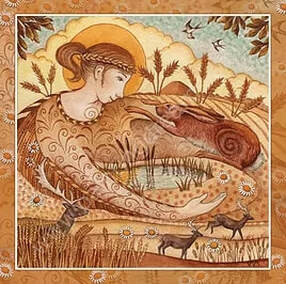

The next I encountered was Epona. Having been shepherded along for years by the three or four I’ve mentioned, I was playing it pretty casual. Epona began to show up, letting me know this was real. Glorious Epona, horse goddess.

When I was pointed to Rhiannon, I knew they were not the same. Rhiannon, who they say, linguistically, might once have been Rigantona, if there ever was a Rigantona. And Teyron – who may have been Tigernonos. But Rhiannon and Teyrnon are enough, surely? But, oh, the Mabinogi! I have learned so much, keeping that under my pillow – a copy in every room of my house.

So much makes sense now. I can almost lay the cards out straight sometimes. Almost. I think back to that encounter I had with Mabon. I get in touch with Maponos. “Divine sons of divine mothers,” they say to me in slightly out-of-synch stereo. I’m fine with that. I’ve been under the earth, seen the prison. I understand the healing there, and the importance of setting it free.

I hear from Macha. Macha of the many Machas. Queens, warrior women, land goddesses – swift, shining ones. Macha of the triple Morrigan (although exactly which three of the four …). Macha, horse goddess, who is not Rhiannon, who is not Epona. I see them travelling together more and more, these days. Herd mothers. Mare mothers. Horse queens.

Macha is looking over my shoulder. Reminding me that we have things to do. Mabon wants us to unblock the healing springs. To unblock the dammed up door to the gods. The door of myth. There is help, and healing, and wisdom behind that door!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed