Padstow, May Day, and the spirit of the Oss

Much verbiage has already been devoted to the origins of the Padstow horse tradition. Like all these customs, the trail of evidence leads us back a few centuries, then the undergrowth closes in and the trail is lost. As far as written records go, hobby horses are first recorded in England in the 15th century as part of court entertainments, and the Padstow custom is first mentioned in 1803, but the wording of this record indicates that the custom is older, just not how much older.

There is always a danger in assuming that written records can tell us everything, just as there is a danger in arranging the past to suit our fantasies. The Padstow May Day celebrations have been subjected to both these approaches, and pretty much everything in between. In the first half of the 20th century, folklorists concluded that the goings on at Padstow were the remnants of a "primitive" fertility rite. As the script of the fascinating, if somewhat cheesy, 1953 documentary "Oss Oss, Wee Oss" says at one point, "I can't say whether it's Druidic or Neolithic, but you gotta admit, this Padstow horse dance is pretty terrific!" (And so it is!)

We have Sir James Frazier and his proto-neo-Pagan blockbuster The Golden Bough to thank for these conclusions. Frazier's thesis was that all early religions were centered around fertility and the worship and sacrifice of kings, in one form or another. Like so many people who hit on a good theory, he began to see evidence of it in unlikely places, and by the time The Golden Bough was into its third edition, and he had calmed down a little, many less critical thinkers had applied his theory to anything and everything.

As early 20th century enthusiasts began to collect and classify the many "eccentric" local customs that existed, they became fascinated by them in their own right, but also began to see evidence of Frazier's theories in them. It is important to say that Frazier's ideas had some basis in fact and reasonable conjecture, and that these early folk enthusiasts were probably right in their perceptions of some customs. What they lacked, was proof, because proof is hard to come by. Customs of the common people were little remarked on during most of history, except when they had a brush with either the church or the legal system. However, early folklorists didn't have to worry too much about written evidence. Their theories weren't really of much interest to the general public, or most of academia, because folklore is a tiny minority interest in the grand scheme of things. For the "folk" having their customs studied, however, the folklorists and their ideas were significant.

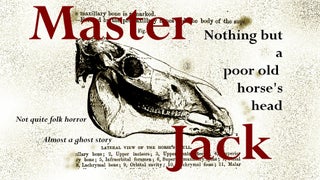

Padstow's May Day customs are particularly robust and unusual. The hobby horses, or more correctly obby osses, to give them their Padstonian name, are so stylized as to be hardly recognizable as horses, until you relate them to the hoop type shown in a couple of old pictures, and still used by the Abbott's Bromley Horn Dancers. The celebrations have both their "reverent" side - in the singing of the night song, and their "wild" side, in the dancing, drinking and horsing around through the streets on Padstow during the day. There are mysterious death and rebirth elements in the dance, too.

| Abbott's Bromley Horn Dancers - photobucket |

There's nothing like a bit of notoriety, though, to get the juices flowing. It's hard to get a clear sense of all the effects that being studied might have on a folk custom, but it's bound to introduce a new element of self-consciousness. The fact that it was deemed "ancient" was definitely a point of pride, and easy to believe since no one could remember a May Day without it. The fertility part was hard to argue with, since it was widely held that any woman caught under the skirts of the horse would soon fall pregnant, or "be married within the year" as people coyly put it back then. As for the Pagan part, well, it probably caused a bit of consternation in some quarters, but mostly just added to the mystique of the thing.

Then, of course, there was the tourism. Oft filmed by the BBC and Pathe news reels, the attention of the folklorists brought more and more curious onlookers to Padstow as the 20th century rolled on, all come to experience the "Pagan rite". In the 21st, this has reached such a pitch that there is barely space for the osses to dance in Padstow's narrow streets. This will probably reach a tipping point before too long, and the tradition will either change shape or they will decide to keep the crowds away somehow.

Padstow's May Day tradition, however old it is, has always been changing. I have been reading some of the main commentators, and I find it amusing to see them so puzzled by the differing reports of observers from different years. They seem so terribly surprised that things are different from one year to the next. The teaser (the person who partners the horse in the dance) is a man dressed as a woman! Wait, the teaser is a man! Now the teaser is a woman! These early folklorists have difficulty with the people of Padstow casually changing things from year to year to suit themselves, and sometimes even tell them they're doing it wrong. If anything, I suspect that the interest of folklorists may have slowed the rate of change in the actual singing and dancing, even though it is partly responsible for the level of outside interest. When you make people aware that they are upholding an ancient tradition, and they know that the world is watching, it is bound to have an effect on that tradition, and one likely effect is a desire to preserve it.

By the 1970s, a new, more serious kind of folklorist had arrived on the scene. One who didn't want to get laughed out of their university department for asserting anything they couldn't prove. They made it known that there was no evidence for ancent origins in the obby oss dance, and that without evidence there is nothing except wishful thinking. Word of this did get 'round the Padstow locals, and not wishing to appear ignorant they accepted it on most levels, but have never completely let go of the Pagan fertility rite theory. A cynic might point out the immense revenue from tourism that comes their way, and that probably plays a part, but I think there is also both an element of pride, and an element of doubt that the folklorists' second opinion is any more correct than the first.

The scientific approach to folk customs has its merits. It's rarely helpful to believe things that aren't true. On the other hand, the romantic, or we might call it intuitive, approach has its merits, too. Especially on the ground, where the folk customs actually happen. In the early 20th century, when most Padstonians would have been regular church goers, they, for some reason, chose to embrace the news that their tradition was "Pagan" and just get on with the business of continuing it. I can't help wondering what chord that news might have struck with them at the time. What did they sense about their own, familiar tradition that they didn't necessarily say? More conjecture. I won't go there.

I know what I feel, as a romantic, intuitive, but fairly level-headed Pagan, when I see the Padstow osses. I see a little piece of the cult of The Great Mare come to life. I don't need to believe that the tradition is unbroken, or that the people of Padstow are secretly all Pagans, to feel that. I believe that a tradition like this carries an energy of its own. One that is far more than the sum of its parts, or even the intention of its participants. For whatever reason, and in whatever way, the people of Padstow help create that energy, and at their best, they channel an energy that wells up from their Cornish souls, and from the ground under their feet, on May Day.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed