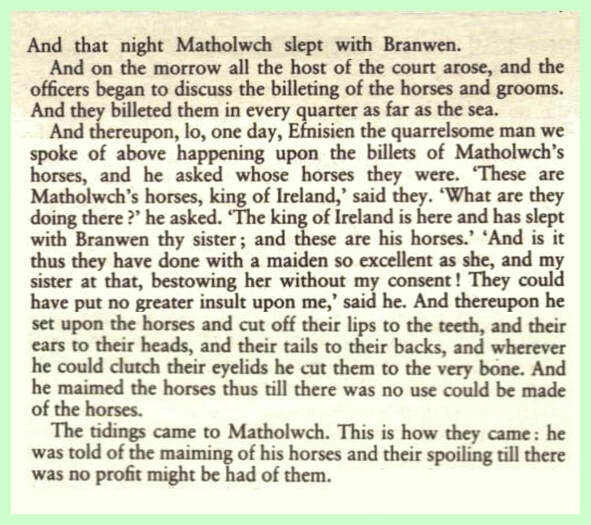

Matholwch, King of Ireland arrives on the coast of Wales, bringing 13 ships full of men and horses. He asks Bran for Branwen's hand in marriage. This is agreed, and the marriage feast takes place. This short excerpt from the Jones and Jones translation takes up the action, which I prefer not to have to paraphrase...

However, let's finish the tale:

Naturally, at this point in the story Matholwch is offended and angry, but Bran manages to patch things up with gifts and apologies. However, as the story unfolds we find that the repercussions from Efnisien's actions have barely begun.

Back in Ireland, Branwen bears a son, called Gwern, but resentment against the Welsh over the mutilation of the horses resurfaces, and in retaliation Matholwch forces Branwen to live as a mistreated kitchen slave. When she manages to send to Wales for help, Bran raises a huge army and invades Ireland.

Seeing himself greatly outnumbered, Matholwch swears to give Gwern sovereignty over Ireland in order to make peace. Bran says this isn't enough, so the Irish offer to build a giant feasting hall, large enough to accommodate him. This is accepted, but turns out to be a trap. The Irish warriors are lying in wait, hiding in supposed flour sacks. Efnisien systematically crushes their skulls with his bare hands, unknown to Matholwch.

At the feast, Efnisien throws Branwen's child, Gwern, into the fire, killing him. More fighting ensues, with great losses on both sides. Efnisien dies by breaking a magical cauldron, Branwen dies of a broken heart, and Bran is mortally wounded by a poisoned spear. In the end, only seven of Bran's army return alive, including Manawydan, Taliesin, and Pryderi - the son of Rhiannon.

This is a very brief synopsis, but I have tried to mention everything, and add nothing. Whether one looks at my short re-telling, or the story as it stands in the second branch, every event, every nuance is open to many interpretations. That is the nature of myth, and I can only tell you what I am thinking at the moment.

Horses, the land. queens and sovereignty are closely bound together in the Mabinogi, and to some extent in Irish texts, too. Exactly how this thinking evolved through time is impossible to say. I suspect that it runs all the way back to a time when humans developed some kind of spiritual or magical relationship with horses as prey. This evolved as horses were gradually domesticated first for meat, and then were both ennobled and enslaved for warfare and heavy work.

Humans are adaptable and innovative, but paradoxically their societies are remarkably resistant to change. If the wild, swift and free horses who were hunted for food were venerated in some meaningful way, how did people feel about taking that freedom away? What stories did they create to make this acceptable, and who within these societies was driving these changes? Was the mare already a kind of earth mother deity? Did the changing status of the domesticated mare mirror, or alter the balance of power between male and female in human society?

I can't help feeling that Celtic stories carry some coded message for us. A distant echo, if you like, of how humans came to terms with or even excused, their changing relationship to nature. Did we change an association between the horse and the earth mother into an association between the horse and our new ideas about owning them, and holding territory for them to graze on?

These gradual adaptations must have brought spiritual or religious adjustments with them. Perhaps during times of change there was a sense that humans might be transgressing natural/sacred laws, or at least that they must be careful to continue to show respect for what had been sacred under the old system. The need to conflate the sacred earth and the sacred feminine (equine and human) and with the holding of territory would have been a philosophical balancing act. One which introduced the need for a more concrete idea of sovereignty.

So how is this echoed in the Mabinogi? In the first branch we have the well-known story of Rhiannon, who is more insulted than abused. Pwyll, although rather inept, makes some attempt to show respect for her, and things are resolved to bring about a happy ending to the story.

When we come to the second branch things shift. While there is a similar tale of the mistreatment of a woman who should be an honoured bringer of sovereignty, she is no longer directly associated with horses. The suffering of these divine queens following their marriages is bad enough, but pales in comparison to Efnisien's mutilation of the horses and the catastrophic events that follow. In the first branch, the insults to the sovereignty bringer, Rhiannon, are the result of Pwyll's foolishness, and while painful for her, impact only her. Efnisien's actions, however, are cruel and show a deep disregard for the sovereign earth mother in the form of Matholwch's horses. It is no wonder that the destruction which follows is also on a different scale.

Although the narration of the Mabinogi concentrates on the insult to Matholwch, and the rendering useless of his horses, this emphasis probably has its roots in legal preoccupations and Christian theology. However, the visceral and highly specific description of Efnisien's crime carries a deep sense of wrongdoing against nature and beauty. Perhaps this hearkens back to an atavistic taboo from our earliest beliefs. The pain and terror inflicted on these horses is an immediate shock to anyone who hears the story. Perhaps we should look into this wound, rather than turning away to focus on the romantic tragedy of Branwen.

It's as if the second branch is saying to us, "Listen. I don't think you fully comprehend the importance of the lesson of the first branch. Let me show you again, more vividly. Let me remind you that there are limits." Efnisien has overstepped the limits of both intention and severity. In the first branch, Rhiannon upbraids Pwyll for unfairly spurring his horse, a crime that shrinks in comparison to Efnisien's bloody rampage.

It is no wonder that none of the characters in this story are able to fix things. Neither sweet Branwen with her tame starling, nor two kings alternating between war and placation, nor Efnision's last minute attempts at heroism can alter the outcome. Men, horses, kings, heirs and kingdoms, the precious cauldron of rebirth and the divine queen herself are lost. At this time in history when those in power seem to have lost all sense of the sacredness of nature, but are leading us to destruction while they squabble over riches and insults, this is a story we need to revisit.

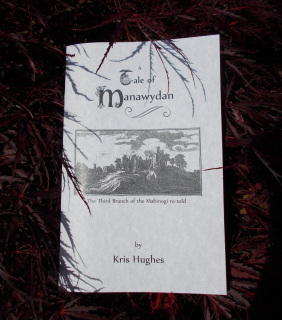

A chapbook containing my original re-telling of The Third Branch of the Mabinogi from the point of view of Manawydan himself. This is a work I never imagined I would produce but the urge to tell Manawydan's story became too strong to resist, so here it is!

8.5" x 5.5"

25 pages

RSS Feed

RSS Feed