Most scholars of the Mabinogi(on) will tell you, “Oh, don’t use the Charlotte Guest translation. Get something better!” I firmly agree, but I think it deserves a bit of an explanation.

Many people cut their teeth on this translation. It was the first translation into English that was at all popular. In fact, it became extremely popular, arriving during the Victorian era, with its obsession with Medievalism in art and literature. Pre-Raphaelite painting, the poetry of Tennyson – it was a perfect fit. Guest’s language is high toned, old-fashioned, and sometimes very beautiful.

Cut to the present day, and Lady Charlotte’s version also has the advantage of having passed into the public domain. The copyright is expired, so any website that wants to host it, or any publisher who wants to reprint it, is free to do so. No wonder it’s still popular and some readers are very loyal to it. (I get it. I like the King James Bible. The language is pretty, I’m used to it, and don’t really care about the accuracy!)

It’s just not a very accurate translation. The reasons for that are varied, and not always as straightforward as you’d think. Guest was not a native speaker of Welsh. However, she was a scholar of multiple languages and took advice from native Welsh scholars during the process.

Most of the later, serious editors of her work have said that the translation was better than they had been led to believe. That said, scholarship of Middle Welsh really has improved since Guest’s day, and all of the later translations reflect this.

| Another concern is the squeamishness about all things sexual which beset so many translations of Celtic texts in this era. There are multiple mentions of couples sleeping together in the Welsh text. As these are often at the consummation of marriages – they just “get married” in Guest’s work, but she hedges if they aren’t married. Other ‘naughtiness’ is also censored out – especially in the Fourth Branch. Most translators of the period would have done the same. Now they wouldn’t. Times change, but these things do affect the overall meaning of a story. |

Guest certainly came under fire (some of it seemingly unfair) from the translators who followed her, most notably Jones and Jones. Being a woman may have made her an easier target than a male translator, or may have caused them to take her less seriously, but I wouldn’t like to go out on a limb over that, because I don’t know what was in their minds.

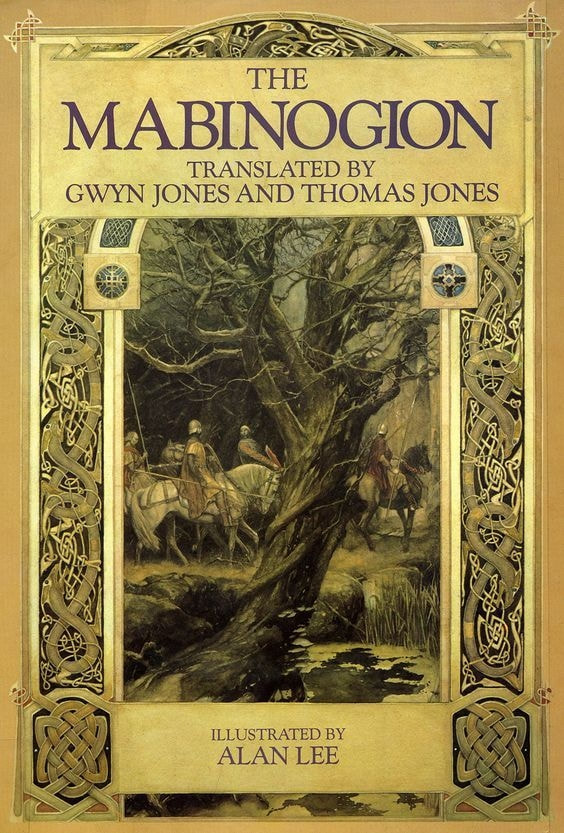

| I think there could also have been some discomfort with Guest’s English nationality, and possibly also her class. The rise in interest in Welsh literature and folklore in Wales was entangled with both important working-class political issues and language justice/nationalism movements. It is perfectly understandable that by the 1940s, when Jones and Jones’ translation appeared, there was an appetite in Wales for a translation produced by Welsh-speaking scholars from Wales. It is perfectly possible that (probably mostly unconsciously) some of these feelings have lingered in Welsh academia. Most modern Welsh scholars will now recommend Sioned Davies’ excellent 2008 translation, so perhaps we can now rule out misogyny. The fact that they tend to offer it in preference to modern translations by US-based Celtic scholars Patrick Ford or John Bollard, may be more a matter of familiarity than national pride. Certainly, Ford is widely respected and his 1977 translation had a good run as ‘the scholarly one’, although it doesn’t include all eleven stories. |

Charlotte Guest was quite a woman. Polyglot and polymath. An example of a member of the upper class who used her leisure time for good works and large projects – including translating a massive piece of literature from Middle Welsh. She also worked to provide education for local children, started a library, and took over the running of her husband’s iron works after he died. (Not to mention having ten children.)

| But for our purposes, Lady Charlotte Guest’s greatest contribution is certainly her translation of The Mabinogion. (And yes, I’m sidestepping the whole issue of that word.) It may have been timing or it may have been money and influence, but neither the English translation by William Pughe in 1833 nor the one by Ellis and Lloyd in 1929 became at all popular. Would we have many of those Pre-Raphaelite paintings or Tennyson’s body of Arthurian poetry without it? Would anyone even be interested in The Mabinogion today, or would it have slipped into obscurity? I can’t answer those questions, but it’s something to think about. |

The Mabinogi: Looking at different translations. A description of all the modern translations, and where to find them.

The Crimes of Lady Charlotte Guest and The Further Crimes of Lady Charlotte Guest are two papers by Donna R. White, delivered to the Harvard Celtic Colloquium in the 1990s, which explore the accusations levelled at Guest and their veracity.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed