______________________

In my second year I was wild and fleet of foot and often caused trouble by breaking away from the flock when the men moved us about for one of their yearly rituals. I learned to be dipped and dosed and shorn. I learned the rollicking time of the tupping paddock, and the long, tiresome winter that followed.

In alarm I panted in the lambing pens, and endured the prodding of a human, while I longed to be out on the clean hill, hidden by a gorse bush, keeping my lambs safe, keeping them all to myself. I could see the patient acceptance of the others as they experienced these indignities. I could see that some ewes and lambs needed the help the shepherds gave them. I felt my milk run and followed the course of its stream back through my mother and grandmother, and outward and forward through myself, my daughters, and sisters, and I felt good.

Then suddenly every gate was opened and we were out! I was calling loudly to my lambs to stay close. Every other ewe was doing the same. Soon we were back under the sky and eating the grass. It tasted so sweet! It was hard at first, not to be anxious about my lambs. I stayed close to ewes I knew well, and for a few weeks we spent as much time calling our lambs as we did eating grass. Summer settled in and we ate our fill of every good thing. I was very proud of my two lambs, they were growing fat on my milk, and learned whatever I showed them with ease.

In late autumn, with new lambs just starting inside us, many of us were driven into a moving box and taken to a frightening place. We were herded into pens and could see and hear many strange sheep and people. We couldn't understand what was happening. My daughter was with me, and I followed my mother and the other friends I had always looked to for guidance, but they were also afraid and lost. Soon we were driven into another box that smelled very strange. In the evening we were put into an unfamiliar paddock with long, rank grass. We have not seen Glen Blackie since then.

We are confused and fearful in the new place. There are many fences. Some that you can run through, and some you can't. We don't know where to go and where not to go. Nothing makes sense. When we see this new shepherd and his dogs, he is usually fast and angry with us. There doesn't seem to be a way to get back to Glen Blackie. Winter has been mild; my lambs will be born soon. Here, in this new place, my milk will run for them.

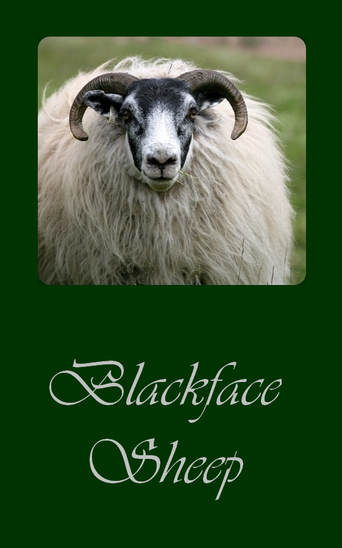

What I understand from the Blackface Sheep is the value of native knowledge of one's environment. If you are a city dweller, you know how useful it is to be a bit streetwise. If you are a country person, it's helpful to understand the rhythms of the agricultural year, and the tasks that are going on around you, even though you might not be a farmer yourself. We need points of reference: where to find the things we need, how things work in our world and who our friends are. Some of us know our environment well, but many of us are struggling with new environments or unfamiliar cultures. Sometimes we need to pause and recognise that such changes may be unsettling us more that we think, and to look for sources of knowledge both within ourselves and without, that can help us to re-orient.

This animal also speaks to me of the importance of recognising and honouring intelligence, in ourselves and others. Intelligence isn't just formal education. It isn't as simple as an IQ test. It is also being able to read situations, knowing what is appropriate in the moment, knowing how the world works. Sometimes intelligence is knowing when to patiently put up with things because tomorrow will be another day.

Maybe you're surprised that I see all this in a sheep, but give it a try. Pick something that you understand and see what it has to show you. I'd love to hear about your revelations in the comments!

*Hefted flocks of sheep know the boundaries of the grazing rights of their owners without being fenced in.

If you enjoyed this post, you might also like The Garron's Musings.

In depth reading by email.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed