| ||||

The problem has always been how to find those stories. Like many Irish texts, dindshenchas are scattered through various manuscripts, giving groups of them exotic names like The Bodleian Dinnshenchas, the Rennes Dindsenchas, and The Edinburgh Dinnshenchas, depending on where the manuscript was housed. And that’s just the prose dindsenchas. In the style of many Irish texts, there are also poetic settings of many of the stories, known collectively as The Metrical Dindsenchas.

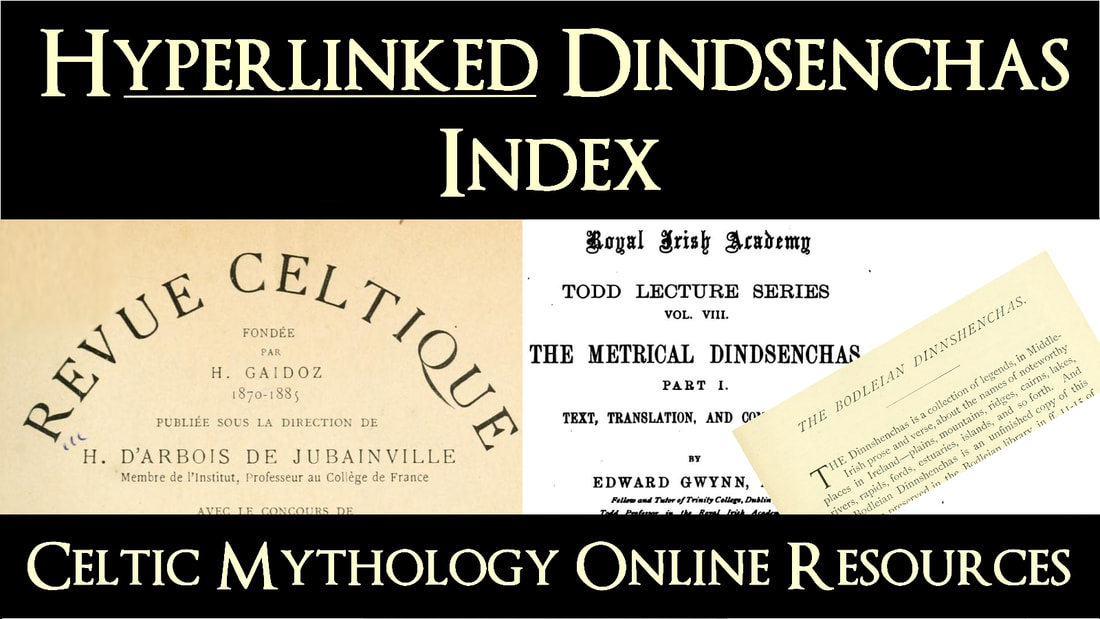

If you’re lost already, wait until I tell you about the English translations! Between about 1892 and 1924, the redoubtable Whitley Stokes and Edward Gwynn (working separately) edited and translated the prose and metrical dindsenchas, respectively, for our use and benefit. Like many translators working at that time, their work was published, often piecemeal, in Celtic Studies journals like Revue Celtique or Todd Lecture Series, where it has remained largely inaccessible to the general public.

Even if you manage to locate the journals, finding your way around the dindsenchas, themselves, can be a bit hit-or-miss. Most of the titles refer to places names which have changed over the centuries, and which give no clue as to what gems may lie within. Who would guess that the entries for Dumae Selga tell the story of the Mac Óc and his lover, Derbrenn, who care for a herd of talking pigs who were once human; or that the dindsenchas of Berba recount the bizarre tale of Meche, son of the Morrigan, and his three hearts? Only the most dedicated students of early Irish texts have really learned to find their way around the Dindsenchas, and it’s no wonder. Some of them are indexed, and sometimes, the index is even in the same journal as the texts. It’s hardly a recipe for a quick browse.

I hope this document will encourage all lovers of Irish myth to explore the Dindsenchas with confidence. They are a wonderful resource!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed