At the feast, things go terribly wrong when a previous suitor of Rhiannon’s turns up during the feast and manages to claim her. However, Rhiannon manages to put him off until “one year from now”. She and Pwyll then hatch a plan to trick the unwanted suitor, and at the second wedding feast their plan succeeds, and they are finally wed.

The couple then return to Pwyll’s kingdom of Dyfed, where they reign “that year and the next” but “in the third year” Pwyll’s advisors begin to complain that Rhiannon has not produced an heir. They want Pwyll to choose another wife, but he persuades them to meet him again “a year from now”, and if Rhiannon has not produced a child, then he will consider it. However, before the end of that year Rhiannon bears a son, who then mysteriously disappears on the night of his birth.

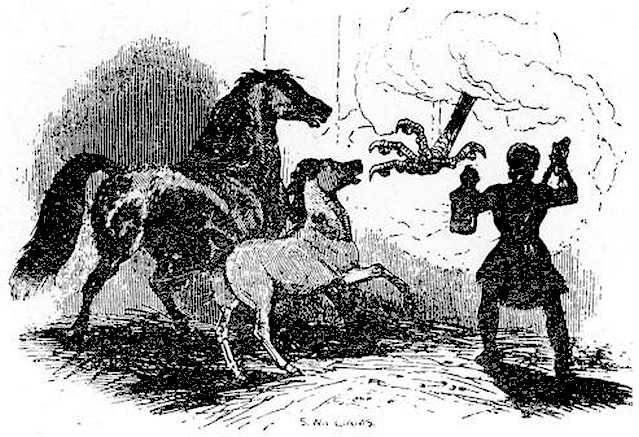

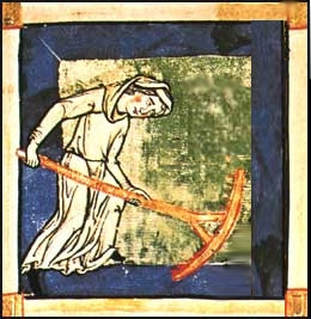

The action of the story then shifts from Dyfed to Gwent, where a landholder called Teyrnon has a fine mare who foals every May eve, but the next day the foal has always mysteriously disappeared. This time, Teyrnon vows to keep watch, so he takes the mare into his house for the night, arms himself, and sits up with her. The mare gives birth and soon a great clawed arm reaches through the window and grabs the foal, but Teyrnon manages to draw his sword and sever it, saving the foal. He runs outside to see what monster the arm belongs to but can find nothing. However, when he returns to the house, he finds that an infant has been left in the doorway.

While May-eve is only mentioned once in the story, at the foaling of Teyrnon’s mare, I feel that there is a strong implication that other major events in the story also take place at Calan Mai. This time of the thinning veil would make sense for Pwyll to go out with the hope of “seeing a wonder”. It is at the beginning of the tale that the language is most explicit that the timings of the wedding feasts are at intervals of exactly one year from the meeting of Pwyll and Rhiannon. This establishes a rhythm of exact years for the subsequent parts of the tale, even though the timing of events might be a little less definite. Perhaps we are expected to get the idea after the first few times.

It seems likely that the birth of Rhiannon’s child happens on May eve, the same night that he is delivered to Teyrnon. If we work back, then we have Rhiannon’s first appearance on the May eve five years earlier, and the return of the child four years later, possibly also at Calan Mai. This motif of years isn’t pronounced in the rest of the Mabinogi, suggesting that it is being emphasised intentionally.

The character of the youthful goddess Rhiannon arriving on her magical white horse is certainly one which feels like spring or early summer, and I don’t think it is hard to envision Her as a May Queen, come to bring good things to the land. It feels very appropriate to me to honour Rhiannon, and Teyrnon as well, at this time of year.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed