“As I walk along this path, therefore, the steps of ghosts hover alongside my own, tracing out other paths beside me. They are ghost paths; the lines of dead legends haunting the landscape, their dim lineaments only faintly visible at the edge of possibility.”

I wondered what I had let myself in for.

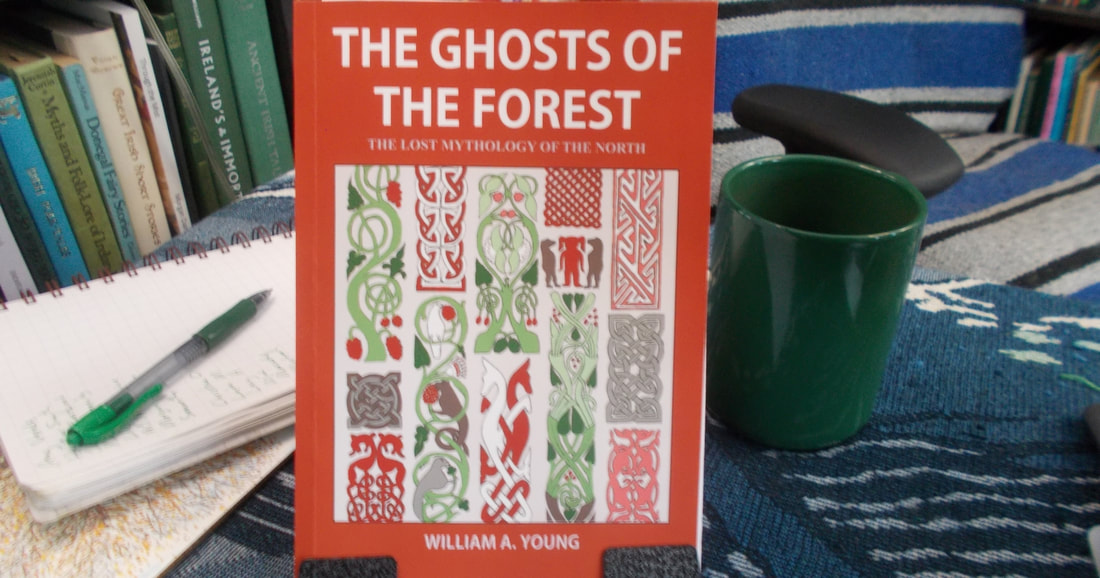

As it turns out, I have not regretted my offer. In fact, I read Ghosts of the Forest cover-to-cover without feeling the need to skim sections and just pretend that I had read them. Like one of the author’s weekend hiking expeditions, the book draws the reader forward into a labyrinthine exploration of landscape, folklore, myth, and dreaming the gods of the Old North into life again.

This book is essential reading for anyone interested in those gods, even though, due to the tattered state of the evidence, most of its conclusions must remain tentative. Not that William A. Young is afraid of a bit of speculation, but it rarely gets too wild. He is generally well grounded and remembers to make those qualifying statements with regularity. I think it’s important to read the book in that spirit. If you go in looking for things to disagree with, you will find them, and if you go in determined to accept every suggestion, you could be misled. But if you read the book in the same spirit of curiosity in which it was written, you will come out with lots of useful leads.

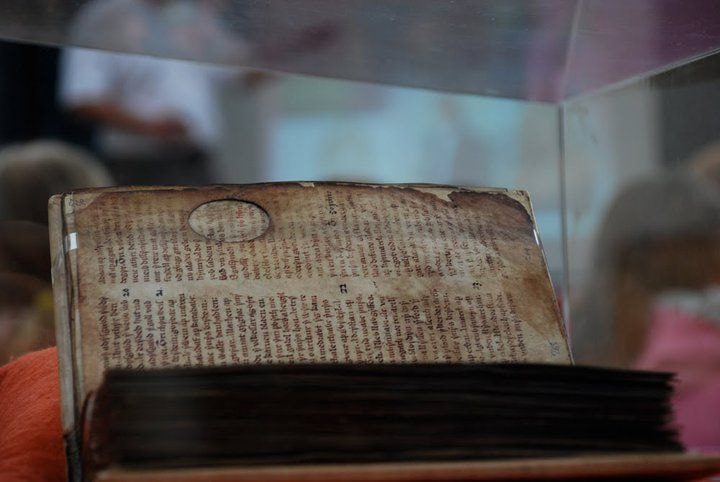

“The ghost-paths never resolve themselves entirely into reality. They are trapped in the space of ‘perhaps’, existing as probabilities rather than certainties; Schrodinger’s wildcats, prowling between the trees. Behind them stalks doubt – the inescapable pursuer encountered on any journey into the history of the Dark Ages. It is a monster that must be confronted repeatedly in the course of any such journey, and it is a fearsome beast. It has devoured any number of academic reputations over the years, stoking controversies and destroying careers in the process.”

This isn’t 600 pages of Young trying to sell you his theory based on increasingly spurious historical references. It’s a lyrical trip through the landscape of Hen Ogledd both in time and space. Young needs to see the places that fascinate him first hand. He needs to touch them and spend the night in them. And he needs to approach respectfully, on foot. To make pilgrimage.

I walk some miles over open, empty heath. Distant rolling hills are all that can be seen on the horizon; in the nearer distance, further herds of sheep and wild goats are in evidence, grazing on the tall summer grass. The land is the definition of emptiness, devoid of human habitation, structures of any sort, even of trees. Pasture alone stretches away to meet the blue of the sky.

Yet, the search for an animistic god is only a part of this journey. There is another treasure to be uncovered here, another portion of the ancient inheritance of this land to be retrieved. This treasure lies concealed not in the destination itself, but in the process of reaching it. The act of journeying into the wilderness was not simply a means to reach a holy place - it was in itself a sacred act.

Not that springs, wells, and fountains are unimportant in the native literature more generally. Like many of us, Young returns over and over to that well, spring, or fountain where we find Owain, Pryderi, and Cynon, having been directed there by a surly guardian of the forest. If this complex of symbols fascinates you, and yet you find that understanding it always ends in a cul-de-sac, then you may appreciate the fresh angle on it presented in The Ghosts of the Forest.

The sun breaks from behind the clouds, and the stones flash white. The warmth of the midday light brushes its hand over the moor, and the green ferns and brown heather tremble under its enervating touch. The sunbeams throw the little figure on the rock into stark relief, lightening the raised portions whilst pooling up shadow in the recesses. As they do so, they illuminate the landscape too, sending the gentler shadows of the clouds chasing across the face of the moor. Colours heighten and fade under their touch, stretches of moor and forest rippling into life and fading into darkness. All is motion - and yet, at the same time, stillness.

The ruinous state of the structure makes it difficult to guess at its original function. What is clear, however, is that it does not fall easily into any known category of building. This was the opinion of Kielder Forest's archaeological surveyor, and my own observations in no way contradict his. It seems likely that it was the source of the stones used in the construction of the curricks; if this should be so, it was clearly once a substantial building, certainly one large enough to qualify as a chapel. Or a temple.

This could be a much shorter book if Bill Young didn’t take us with him on his hill walks. But it seems to be while he’s walking that so many of his good ideas are brought forth. This gives the book a naturalness that wouldn’t be achieved in a more concise format. I did occasionally long for some kind of outline with lots of chapter headings, such as some of the old antiquarian and folklore books used to provide. (If you want to find things again in this book, my advice is to make notes.)

It was in a most handsome, beautiful chapel, in which there was no scrap of timber; it was rather entirely of marble and decorated with carvings. The doors were of ivory and the doorway gilded.

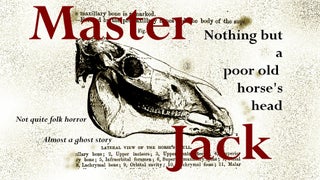

In front of the entrance, was an amazing great churl: you never saw one so hideous. He was cast in bronze, and in his hand, to be sure, he held a huge, heavy steel hammer. If you had seen the churl, you would not have said otherwise than that he looked like a mortal man. ...

Night and day the lion rests in that chapel. However, it quite lacks flesh and blood, skin and hair: instead, it is completely white, beautifully carved in ivory.

- from the author's re-telling of Fergus of Galloway

Two recurrent themes are the author’s call for some of the sites he visits to be better investigated, archaeologically; and his arguments that some form of Pagan religion persisted for many centuries in the North – far beyond Roman Christianity, or even beyond the time of the evangelising saints. Of course, these two topics are not unconnected. Maybe, it would be nice if we could brandish some material proof which would advance the dates of the survival of ‘pre-Christian’ religion in the area. I certainly agree with the author’s instincts that this is the case, and he makes some excellent arguments for it. However, I think this needs to be weighed against the questions of disturbance, notoriety, and increased footfall to sites which currently exist in peaceful obscurity.

The Ghosts of the Forest is available on Amazon in the US and UK, or from the author’s website: inter-celtic.com

As the Romans retreated from Britain, a new dynastic order (or perhaps disorder) rose up in what is now southern Scotland and northern England. Later known by the Welsh as Hen Ogledd: The Old North, its heroic and poetic remembrance is one of the most beautiful, and often overlooked flowerings of Celtic-speaking culture.

In Tales of the Old North we will hear the words of the bards and scribes concerning Taliesin, Urien, Owein, Myrddin, The Gododdin, and more.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed